Eastern Europe

Exploring the Hidden Europe in 2004 and 2008-2011

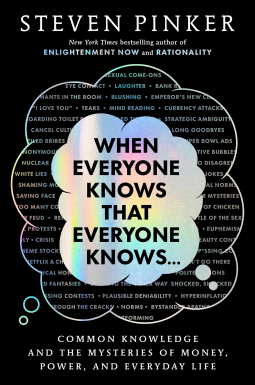

In 2004, I visited all 25 countries in Eastern Europe. You'll find the blog entries from that trip here. In 2008-2011, I returned to see what had changed since that time. With these two visits, five years apart, I accumulated enough material for my 750-page book, The Hidden Europe: What Eastern Europeans Can Teach Us.

This blog now has many excerpts from The Hidden Europe. But who the hell reads anymore? Just look at the best photos from Eastern Europe!

This map reflects how I define Eastern Europe. Eastern Europeans love to deny that they're in Eastern Europe. I tackle how and why I define Eastern Europe the way I do in the Introduction of The Hidden Europe.

Imagine if the Grand Canyon were underground—that should give you an idea of what to expect when you enter the Škocjanske Jame (Škocjan Caves). Lonely Planet listed them as one of the top 10 attractions in Eastern Europe. They’re also on the UNESCO World Heritage list and get 100,000 visitors a year.

Imagine if the Grand Canyon were underground—that should give you an idea of what to expect when you enter the Škocjanske Jame (Škocjan Caves). Lonely Planet listed them as one of the top 10 attractions in Eastern Europe. They’re also on the UNESCO World Heritage list and get 100,000 visitors a year.

They live up to their reputation by being one of the largest underground canyons in the world with the Reka river still carving through it. At 60 meters wide and 140 meters deep, this canyon is a fraction of the Grand Canyon’s size, but the fact that it’s all underground makes it feel bigger.

When you cross the canyon via the narrow Hanke Canal Bridge, you’ll see the roaring river far below. You’ll realize that you could fit a fat 45-story skyscraper in this subterranean world.

The Škocjan underworld is so enormous that a unique ecosystem has evolved here—it’s home to strange blind creatures that have never seen sunlight. The most bizarre one is the proteus.

Slovenians informally call it the človeška ribica (human fish). This alien vertebrate is as long as your forearm, has a long tail for swimming, gills, four legs, pigment-free skin, a highly sensitive nose, a sensor for detecting weak electrical fields in the water, and a pair of atrophied lungs and eyes that don’t really work.

They’re a weird amphibian that lives almost exclusively in water. Their life cycle is mystifying: they live almost as long as humans, they become sexually mature as teenagers, they have never been seen reproducing in the wild, their babies hatch out of eggs, and they can live up to 10 years without food.

It’s one of the most hidden creatures in the Hidden Europe.

While I was traveling in Eastern Europe, my high-school friend, Sarah Spiridonov, made me an offer I couldn't refuse. I hadn't talked with Sarah since we were 18 years old, but thanks to Facebook, we reconnected. She was married to a Bulgarian and they had two boys. To help me with my book, she generously proposed that I stay a couple of weeks in her family's summer home in Turkincha, a tiny village about 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) from Veliko Tarnovo. I was extremely grateful for the opportunity to take a closer look at a rural Bulgarian setting. The experience ended up surprising me in numerous ways.

The village of Turkincha

One Ukrainian tourist website proclaims: “Ukraine is the geographical center of Europe!” And then, confusingly, the first sentence after that title is, “Ukraine is one of the mightiest countries in Eastern Europe.”

Starting in 1999, I visited Ukraine every five years. Each time I returned, Ukraine seemed to have taken three steps forward and two steps backward.

Traces of communism

In 1999, I flew into Ukraine’s capital, which is often called Kiev, but we will use its official name: Kyiv (pronounced Kee-v). I stayed in the Mir Hotel. I learned that mir is a cool Eastern Slavic word that has two meanings: world and peace.

Although communism had officially disappeared nearly a decade before, its remnants were everywhere. For example, every floor of the hotel had a middle-aged, overweight female gatekeeper who was in charge of the floor. Besides having the thrilling task of policing the floor, this stern woman would also hold your keys, which clearly the receptionist in the lobby was incapable of doing. Similarly, at the bottom of every subway escalator, there was a guard whose stimulating job was to verify that life around the escalator was OK. Communism’s goal was to give everyone a job, so it invented millions of useless jobs. Many of these pointless jobs remain.

Another example of a communist leftover was the controlling and corrupt police force. In 2004, when I saw Kyiv’s colossal titanium Mother Motherland statue from far away, I used my camera’s zoom to take a photo. While snapping the picture, a policeman ran up and ordered me to stop. He thought I was taking a photo of a nearby military building that was in the line of sight of the distant statue. I showed him the photos so that he could believe me when I said that I wasn’t a spy.

Another example of a communist leftover was the controlling and corrupt police force. In 2004, when I saw Kyiv’s colossal titanium Mother Motherland statue from far away, I used my camera’s zoom to take a photo. While snapping the picture, a policeman ran up and ordered me to stop. He thought I was taking a photo of a nearby military building that was in the line of sight of the distant statue. I showed him the photos so that he could believe me when I said that I wasn’t a spy.

Although I never faced corruption during any of my visits, in 2010, travel blogger Justin Klein got “shaken down” by police officers on five separate occasions during a short trip.

He offered tips on how to avoid such encounters:

- Keep quiet when the police are around (so they don’t overhear you speaking English).

- If they ask you for a bribe, reinforce that you’re just a poor traveler who is staying in cheap hostels and traveling on second-class trains.

- Say that you’ve already had to pay other officers “fees” for minor “violations.”

- Carry little cash in your wallet (or at least the wallet you show them); they’re unlikely to walk you to a bank to get more money, so you might get away with a small bribe.

- Pretend you don’t understand them and hope they get bored.

Justin nearly left Ukraine early out of frustration, but he’s glad he stayed because he loved the people and the country overall.

Another communism hangover is that arbitrary rules are posted everywhere. Fortunately, it’s all in Cyrillic so you probably won’t understand them, although I learned to spot their favorite phrase, “Strictly Forbidden!” Ukrainians probably ignored half of the rules under communism, but nowadays they seem to ignore all the rules.

The strictness of our laws is compensated for by their lack of enforcement. — Whispered Soviet saying

- Moldova

- Romania

- Bulgaria

- Turkey

- Greek food and language in Thessaloniki

- Reasonably Priced Hotels in Dubrovnik

- Solution to Europe's credit downgrades

- KQED Forum with Michael Krasny

- Innovation in Eastern Europe

- Greece

- Macedonia

- Kosovo

- Albania

- Montenegro

- Bosnia

- Three Sights to See in Prague

- Serbia

- Croatia

- Slovenia

- Hungary

Your comment will be deleted if:

- It doesn't add value. (So don't just say, "Nice post!")

- You use a fake name, like "Cheap Hotels."

- You embed a self-serving link in your comment.