Eastern Europe

Exploring the Hidden Europe in 2004 and 2008-2011

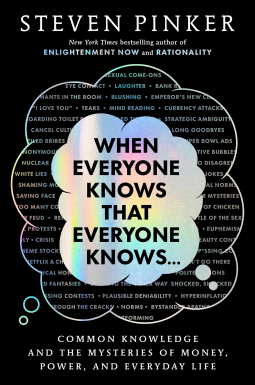

In 2004, I visited all 25 countries in Eastern Europe. You'll find the blog entries from that trip here. In 2008-2011, I returned to see what had changed since that time. With these two visits, five years apart, I accumulated enough material for my 750-page book, The Hidden Europe: What Eastern Europeans Can Teach Us.

This blog now has many excerpts from The Hidden Europe. But who the hell reads anymore? Just look at the best photos from Eastern Europe!

This map reflects how I define Eastern Europe. Eastern Europeans love to deny that they're in Eastern Europe. I tackle how and why I define Eastern Europe the way I do in the Introduction of The Hidden Europe.

Turkey is one of only four countries that want to be associated with Eastern Europe (the other three are Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine).While every other Eastern European country stubbornly resists the Eastern Europe label, Turkey embraces it. And yet, many Europeans don’t want to give Turkey the “honor” of being in Eastern Europe, because they believe that Turkey isn’t a part of Europe.

Geographically, Turkey has only a toe in Europe (see map below). About three percent of Turkey is in Eastern Europe; the rest is in Asia. Because of this lopsided ratio, it’s tempting to exclude Turkey from this book. Still, just like eastern Germany is a legacy member of Eastern Europe, Turkey (due to the Turkish Empire’s dominance in the Balkans for five centuries) is also a legacy member. Moreover, modern Turkey is part of NATO, has strong ties to the Balkans, and is a serious EU candidate. In addition, while only a small part of Turkey lies in Europe, about 10 million Turks live in that part—that’s a bigger population than many European countries. Thus, we must consider Turkey. Nevertheless, we’ll focus on Turkey’s western side—the part that’s most connected to Europe. I plan to analyze Turkey much more thoroughly in Book Four of the WanderLearn Series, which will cover the Middle East.

Before we take our short tour of Western Turkey, let’s consider the country’s name. Several Turks told me that they hate it when their country is called Turkey instead of Türkiye (sounds like Tur-ki-yea). Of course, they wouldn’t have a problem with Turkey if the word didn’t have three unflattering meanings: a winged animal, a jerk, and a flop. If turkey meant awesome, then no Turk would complain. Hungary faces a similar problem with its name. Hungarians call their country Magyarország. Like the Turks, Hungarians are tired of people cracking jokes about their country.

Ethiopia was disappointed with the World Cup draw. They were hoping to get Turkey, but got Hungary instead. — Bad joke

According to my tastes, Greece has the most delicious food in Eastern Europe. They energize their meals with fresh ingredients like tomatoes, eggplant, feta cheese, onions, olive oil, yogurt, zucchini, nuts, and honey. During the Byzantine and Turkish period, Greeks incorporated spices like oregano, dill, bay leaves, and mint.

According to my tastes, Greece has the most delicious food in Eastern Europe. They energize their meals with fresh ingredients like tomatoes, eggplant, feta cheese, onions, olive oil, yogurt, zucchini, nuts, and honey. During the Byzantine and Turkish period, Greeks incorporated spices like oregano, dill, bay leaves, and mint.

Today, popular dishes include souvlaki (anything marinated in olive oil, salt, pepper, oregano and then skewered), dolmathes (grapevine leaves stuffed with rice, veggies, and sometimes meat), and tzatziki (yoghurt with garlic and cucumber). Even their fast food is delicious: gyros (meat roasted on a vertically turning spit and served with sauce and garnishes on pita bread) will make you give up hamburgers. Finally, baklava (phyllo pastry layers filled with nuts and drenched in syrup or honey) is a decadent dessert to end any meal.

It’s all Greek to me

Over dinner, my four Greek hosts gave me a crash course on Greek. Niki was particularly instructive because she has a degree in the ancient Greek language. Basic phrases include yashoo (hello), adio (goodbye), puinne. . . (where is. . .), posho kani? (how much?), tikanish? (how are you?), treno (train), pote (when), tikanish? (how are you?), poli kalo (very good), katalava (understand), signomi (sorry), and, most importantly, efharishto (thank you).

About every 10 minutes Niki (whose name means Victory) loved to remind me that some English words I said were derived from Greek. She could have interrupted me more often: about 12 percent of the English vocabulary has an ancient Greek origin, including words like mathematics, astronomy, democracy, philosophy, thespian, athletics, theater, and rhetoric.

Still, this doesn’t mean Greek is easy for us. Most Greek verbs are irregular. They have four cases. They even have three ways to write their sigma character. The first is upper case (Σ), the second is lower case (σ), and the third is used only when the word ends with the sigma character (ς). Σo σentenceς would read juσt like thiς.

There are two other annoying things besides the Greek alphabet. First, while most European countries use a word that sounds like bus or autobus, the Greeks call that vehicle a leoforio. WTF? Second, to say yes, you have to say neh, which sounds like a negation in most European languages. So when I ask, “So the leoforio leaves today?” they’ll nod and say, “Neh!” Meanwhile, to say no, you say ohhi. As William Shakespeare said, “For my part, it was Greek to me.”

There is a misleading, unwritten rule that states if a quote giving advice comes from someone famous, very old, or Greek, then it must be good advice. — Bo Bennett

After learning about my new book, The Hidden Europe, a reporter from a San Diego newspaper asked me for tips on finding a reasonably priced accomodation in Dubrovnik, Croatia. Because everyone has different definitions of what is "reasonably priced," here are 6 good options to stay in Dubrovnik in 2012:

1. Hotel Excelsior Dubrovnik. Five star hotel outside Old Town. 158 rooms/suites. Price $150-350/night.

1. Hotel Excelsior Dubrovnik. Five star hotel outside Old Town. 158 rooms/suites. Price $150-350/night.

2. Hotel Uvala. It's a 4-star hotel that has rooms that feel like the Holiday Inn. It's near the beach and not in the Old Town. It's $150-250/night.

3. Begovic Boarding House. They have dorm rooms, singles, and doubles. They have a shared terrace with a view. Prices range from $20 to $60.

4. Youth Hostel. Youth Hostel Dubrovnik resides outside the Old Town. You get there after a 20 min walk from the bus station and it takes you 15min to get to the Old Town. Roughly $20/night per person in a dorm-room arrangement.

5. Be spontaneous! This is what I like to do and it works well if you're not hauling around lots of luggage. Look for homes with signs that say "Zimmer" (room, in German) or "Sobe" (rooms, in Croatian). Knock on their door, negotiate with the owner, and then stay with them. You'll stay in a real Croatian home, and you'll usually have your own bathroom. There are hundreds of rooms available in Dubrovnik, both in the Old Town as well outside of it. So you can almost always find a place pretty easily, even during the high season. If they're full, ask them to refer you to (or call) someone else. Obviously, places outside the Old Town are cheaper than those inside the Old Town. Prices vary: $25-50/night.

6. Stay in the Old Town in a 3-star apartment. Croatians will rent out their apartment, especially during the high-season. Rates vary from $75 to $150/night. The advantage is that you're in the Old Town and the price is a great value.

Then the reporter asked, "So, do you recommend staying in the Old Town?"

I replied: I've stayed both in and outside of the Old Town - they are both good options. As you might expect, outside the Old Town you'll get more bang for your buck, because to stay in the Old Town you're paying for the convenience of being in the thick of it. Still, the Old Town is pretty quiet at night, so don't expect loud noises. If you stay in the Old Town, make sure to find out how many steps you have to take to get to your apartment (sometimes it can be over 100).

Wherever you stay in Dubrovnik, make sure you see the other surrounding jewels: the rest of the Dalmatian coast, Kotor (Montenegro), and Plitvice Lakes National Park.

Your comment will be deleted if:

- It doesn't add value. (So don't just say, "Nice post!")

- You use a fake name, like "Cheap Hotels."

- You embed a self-serving link in your comment.