I am in Steamboat Springs, just two days from exiting Colorado. Colorado has ravaged me like a Viking.

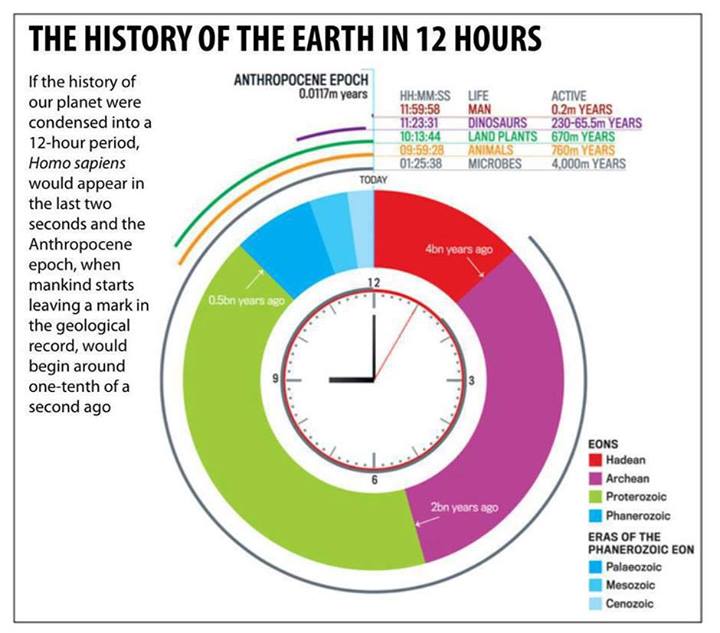

I’ll share two tales that sum up Colorado. However, before I do that, let's sum up our planet’s history in an unusual way. I think about this often and it is one of the tricks I used to keep me going in challenging times.

The Pilgrim's perspective

Many people ask me, “What are you thinking about when you walk from sunrise to sunset in remote wildernesses?”

Sometimes I’m just thinking of the next step. Other times I’m thinking about Megan Fox.

However, during my pilgrimage, I do go into deep-thoughts mode occasionally. That’s what this article is about. It will lead to my next article which is about what it means to be human and my debate with a T-Rex on global warming. Yeah, light topics. Can’t I just talk about the weather?

One of the aspects that I love about thru-hiking is the sense of perspective it gives you. Most humans are stuck in day-to-day drudgery, incapable (or unwilling) to break the chains of their self-centered, short-term point of view. I confess I’m no better than the average Joe and that missing one synchronized light can really send me into a deep depression.

However, when I travel for months in the mountains I can’t help but have a broader perspective. For example, when I am walking a ridge on the Continental Divide, its history is etched into the landscape.

Although the Earth is 4.5 billion years old, the planet didn’t really start to settle down until it was a billion years old. And life didn’t really get going until the Pre-Cambrian era (over half a billion years ago). However, it is nearly impossible for my puny human brain to relate to that much time. Actually, a million years is too hard to imagine, even if I compare it with how long my bank puts me on hold.

Therefore, to crunch world history into a timescale that I can fathom let’s squeeze it into one calendar year. And I’ll focus on the development of the Continental Divide Trail (CDT). Here’s what we get.

Earth's history compressed into one year

January and February would be good months to stay in your cabin. The Earth’s environment was chaotic. Incessant wind and rain would erode away barren mountains faster than a plastic surgeon can erode away Michael Jackson’s nose.

Still, on February 25 (or is it February 30?), life would spring forth! Sure, these single-celled organisms would be stuck in the warm coastal waters and by the thermal vents, but we’ll take what we can get.

March 20: Stromatolites would pop up.

July 17: Multicellular life, those cells with nuclei, were strutting their stuff.

Trilobites (hard-shelled creatures) would start feeding on all the multi-cellular life. By the end of the month, small vertebrates would start feeding on the Trilobites. All you can eat restaurants were invented.

Most of the year would go by and still no life on the land.

Where would the Continental Divide be in October?

It wouldn’t be a thrusting mass of mountains that I walked. Quite the opposite! It would be a broad channel of water. You could ride your kayak down the channel!

In fact, if you flew over North America in June, you’d see that 60 percent of the land is underwater.

Would you see forests of trees on the land? Nope, you wouldn’t even see moss clinging to the ubiquitous rocks. Zero plant life. However, it wouldn’t be a static boring rock-filled landscape. It would be constantly eroding, pummeled by endless torrential rains that make the south-east Asian monsoons seem like a drizzle.

The Continental Divide would be impossible to recognize in early November. Instead of the Rocky Mountains stretching out as far as the eye can see, you’d see a massive sea that stretched from the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico!

In early November, the first plants would gain a precarious foothold on land. For every plant that latches on the land, many will get washed away by the endless rain. The struggle of the plants to get established lasts for weeks, but they finally settle down. Vegetarians aren’t far behind.

On November 18, the Cambrian Explosion - a burst of complex life - would roll out. In a couple of days, the seas are crowded with fish. A few claustrophobic ones develop crude lungs, call themselves amphibians, and get timeshares on the land.

Around November 20, the Appalachian mountain range starts to rise and will be far higher than any other mountain range in the USA today. You wouldn’t find cozy shelters every 15 kilometers on the Appalachian Trail.

December 5: First reptiles.

December 12: Doh! The Permian Extinction, the most deadly event in Earth's history, happens. Siberian traps (big volcanoes) spew up so much toxic smoke that 95% of life on Earth dies.

December 13: Dinosaurs appear.

December 14: Dinosaurs chase the pathetic-looking mammals that just start to appear. The dinosaurs thought these mammals were snacks since few were much bigger than a rat.

December 22: Plants with flowers appear. It's about time!

December 26: The planet's post-Christmas presents are cats and dogs. Cute puppies and kitties. The most memorable event of this day is when an asteroid the size of Manhattan Island strikes the Yucatan with a force of 100 million megatons. The impact would release a heat pulse that would set off fires across the planet. The result: a planetary dinosaur barbecue. Their “two-week” reign comes to an abrupt end.

December 27: Grasses spread like fire across the earth. Pigs and deer follow. The Rocky Mountains would finally start to rise and tower over the surrounding land. The CDT wasn’t well marked then either. The Colorado River would start its tedious process of slicing the Grand Canyon.

December 28: First primates jump through the trees.

The sun would rise on December 31 and still no sign of humans.

Finally, at 17:18, somewhere in Africa, the first clumsy hominids would stand up. During the last hours of the year, you’d see massive sheets of ice, as tall as mountains, cover America and Euroasia. Like an accordion, you’d see the ice sheets (glaciers) come and go four times in just a few hours. It would look like a global warming yo-yo gone wild.

With one hour to go before the year ends, Homo erectus shows up to the primate party.

At 23:30 the French start showing off their artistic talent: Cro-Magnon man draws cool paintings in some caves.

At 23:45 homo sapiens figure out how to make weapons of mass destruction: sharp knives and spears.

Around 23:55 civilization begins. Prostitution shortly follows. Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans each spend a minute building touristy buildings.

At 23:58 and 43 seconds, Jesus tells everyone to behave. We kill him a nanosecond later.

With just 20 seconds to go before the year draws to a close, Columbus bumps into America. Dick Clark is born and starts making a living counting down the seconds to the New Year. “Just 7 seconds to go!” announces Dick, and rebels sign the Declaration of Independence.

In the final 7 seconds, we finally arrive at the crown jewel of billion of years of evolution: Megan Fox.

Whew! Now you know what kind of thoughts run through my head when I’m walking across endless mountain ranges. See, I told you I think of Megan Fox! But usually, I’m fantasizing about Oreos.

Whenever you’re feeling pretty important in your cubical, or you’re pissed off that your spouse is late, or you’re frustrated that you don’t have everything you want, then perhaps it’s time to think about this timeline. James C. Rettie wrote a similar timeline over 50 years ago. I think about this timeline every day during my 5,600-mile walk on the Continental Divide, especially when a lovely rash develops near my groin.

Put your life in relationship to this calendar. Put whatever event that you think is a big deal and place it next to this timeline. Watch its importance shrink to nothingness. This might make you depressed, but it can also liberate you from the shackles that bind most of us to the unimportant issues of the day. It might help motivate you to make the changes in your life that you’ve wanted to make.

Go out and have fun. Hike your own hike. And enjoy the time you have on this lively planet.

If you enjoyed looking at the Earth's timeline compressed into one year, then check out this fascinating post.

To illustrate how I use this calendar, I’ll end this article with two tough tales from the CDT in Colorado…

Tough tale #1: climbing the tallest mountain in Colorado during a snowstorm

The official CDT skirts the base of Mt. Elbert, but I wanted to summit the damn thing. Mt. Elbert is the tallest mountain near the Continental Divide. In fact, if you don’t count Alaska, Mt. Elbert is the second tallest mountain in America, after California’s Mt. Whitney. The lure was too great to pass up.

Normally I check the weather forecast before I leave a town, but I forgot to do that when I left Twin Lakes, CO. While I slept calmly at the base of Mt. Elbert, I had no idea that a major snowstorm was headed my way.

I woke up at 1 a.m. to get a headstart on the 14,440 ft (4,401 m) mountain. I wanted to hike through hard, frozen snow so I could get up and down the mountain quickly. As soon as I got above the tree line, it started snowing. The higher I climbed, the windier it got. A dense fog settled in while it snowed, creating whiteout conditions and limiting my visibility to 10 meters.

In short, I had the worst conditions you could get on Mt. Elbert in May: sub-zero temperatures, high winds, snow, and whiteout conditions.

Stubbornly (and stupidly), I continued to climb.

After a few hours, I wondered if I was climbing the right mountain. With the whiteout, I had no idea what mountains were around me, so I couldn’t get a reference. My altimeter was steadily going up: 11,000 ft… 12,000 ft… 13,000 ft… 14,000 ft…

But I knew there were other 14ers in the area. Finally, my altimeter showed 14,500 ft.

“OK, I know that’s wrong because Mt. Elbert is only 14,440 ft and I can’t be higher than that unless I’m jumping 60 feet in the air!”

However, air pressure had been dropping during the snowstorm, which would artificially boost the elevation my altimeter displayed. Was I on the right mountain?

I climbed a few more feet and found a three-meter wooden stick planted at the summit. It had names engraved in it. It didn’t say anything about Mt. Elbert. I didn’t see a register. I remained confused.

Fortunately, the snowstorm abated a bit and so I could quickly take a few victory photos. I felt odd because I wasn’t even sure I could declare victory since I wasn’t 100% sure I was on Mt. Elbert. Occasionally, the fog would lift for a few seconds and I could see mountains below me and nothing above me, but it was hardly conclusive.

“Well, in the worst case, I climbed some big 14er,” I told myself as I began to descend.

Within 30 minutes, the snowstorm intensified. Thanks to the blizzard I got lost on my way down and wasted a couple of hours wandering aimlessly around the mountain, post-holing often. Finally, I found the CDT and got down to the lowest point I could go: 10,200 feet, relative safety.

I had reached Mt. Elbert, but I didn’t come down with much wisdom.

Tough tale #2: stuck between a rock and a cold place

I started climbing at Berthoud Pass, heading toward Rocky Mountain National Park. Most of the day I avoided walking the official Continental Divide Trail (CDT); instead, I preferred hiking the actual Continental Divide. The CDT often doesn’t stay on the geographic Divide for several reasons, including lack of water, craggy ridges, and massive exposure to the elements.

However, it is one of those elements (the vicious wind) that encouraged me to hike Divide and stay off CDT. The Divide’s violent wind blows the loose snow off the ridge. Moreover, since the Divide is above the tree line, the snow is always exposed to the sun’s rays. The combination of strong wind and sun makes the Divide’s snow hard and crunchy. The CDT, on the other hand, often stays below the Divide, under the protection of trees. That is wonderful in the summer, but in May that translates into snow that is deep, soft, and slow to melt.

I had little interest in postholing (when your foot/leg breaks through weak snow and you’re knee-deep into it). Therefore, I stayed as high as possible by following the Divide. I spent most of my day around 13,000 feet and I could walk faster than on the snow-filled CDT since the snow on the Divide was either hard or gone.

However, as the sun set, I had no place to camp on the Divide. I use an MLD tarp and I don’t carry trekking poles. Normally I always find trees to attach it to, but there aren’t any trees above the tree line. The rocks on the Divide were all too short to be a useful anchor for my ridgeline. Although I could descend a thousand feet to camp in the trees, I could see that the ground down there was entirely covered in deep snow.

Hence, my dilemma: I could either camp high, getting buffeted by cold 40 mph winds, but be on dry rock, or I could camp low, away from the winds, but sleep on deep, soft, wet snow. And you thought choosing between Bush and Kerry was hard.

I decided to camp high. By 9 p.m. I found a large rock to anchor the tarp’s ridgeline. I planned to use my ice ax to anchor the other side. The howling winds sucked my heat away and made it hard to control the tarp. Imagine trying to anchor a parachute while you’re freefalling through the sky.

After 10 minutes, I was shivering but I finally got one anchor down. My clumsy cold fingers struggled to get the other ridgeline attached to the ice ax. I finally got it and then tried to shove the ice ax into the ground.

Thump! Nothing. The ground was hard as a rock, because, well, it was made out of a rock.

When I picked that spot I stupidly didn’t consider that I wouldn’t be able to get the ice ax into the ground. I had wasted precious time and had lost all the heat I had generated while hiking. I was frigid and I still had no place to camp. Descending the mountain to wade through waist-deep cold snow was still not enticing. I pressed on, staying on the Divide.

By 10 p.m., I was navigating by moonlight. The 40 mph winds were steady and getting colder. I hiked vigorously to ward off hypothermia.

I finally found a jumble of large rocks that seemed promising. I wedged myself in between them and immediately smiled as the constantly screaming wind fell silent.

It was a pathetic and awkward place to call “camp,” but it was the best thing I had found in the last five hours. I curled into my Jacks R Better sleeping bag and fell asleep at 12,000 feet.

Two hours later, around midnight, I woke up shivering. I tried warming myself up by tensing my muscles and rubbing my body vigorously. Within minutes I was cold again. I finally figured out what was going on. The Jacks R Better sleeping bag is really a quilt, so your bottom is exposed. Although I use a pad, there were random openings in the awkward jumble of rocks. The icy cold air was seeping through these crevices. I hadn’t noticed them when I first got there because I was comparing it to being exposed to the 40 mph winds head-on. However, the crevices created a slow leak that threatened me with hypothermia in the sub-zero temperatures.

I couldn’t start a fire because there was no wood above the tree line. I couldn’t stay put because I losing heat. Therefore, having only rested for two hours, I packed up and started hiking at midnight.

The moon illuminated my way until 2 a.m. when it set. I kept hiking, using the stars as my light. I stumbled often on the loose rock. The wind was merciless – it never stopped biting into me all night. And I never stopped walking. The sun rose, I kept walking. I walked nearly 50 miles over those 35 hours. I eventually got to Grand Lake, where I could rest.

Colorado challenged me many times. Each time the trail got tough I would think about the timeline that I described above and it would comfort me. I reminded myself that these trials are fleeting events. I focused on the big picture instead and that kept me happy and positive. The double dose of Prozac helped too.

Setting a Record

I’m almost certain that nobody has ever thru-hiked the CDT section of Colorado (about 740 miles) during the month of May. I entered Colorado on May 2 and I am exiting on May 30. So for what it’s worth (not much), that’s a little record that everyone will forget about after I’m dead.

By exiting Colorado, I’m also past the halfway point to Canada. That means I’m 25% done with the CDT yo-yo. Moreover, the toughest part of the yo-yo (Colorado in May) is now behind me. The last 75% should be easier.

Indeed, I’m looking forward to Wyoming in June. It should be everything that Colorado was not: hot; dry; and relatively flat. Woo-hoo!