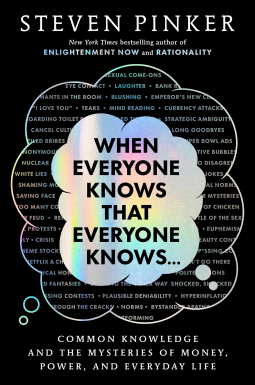

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows is Steven Pinker's worst book, but it's still fascinating, especially if you're into logic and puzzles.

Disclosure: I've read all of Pinker's books, and I gave them all five stars. I graduated from Harvard, where Pinker teaches. I received a free advanced copy of Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows from the publisher. None of these factors biases my judgment: I give this book 3.5 stars.

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows is available on September 23, 2025. Pre-order it now if you find this review captivating.

The book's publisher, Simon & Schuster, doesn't want reviewers who received an Advanced Review Copy to quote from the book, because it's always possible that the final version will differ. Nevertheless, I'll quote from passages that illustrate the book's main points. Even if the publisher deletes these passages in the final release, they're still indicative of what the book is about.

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows is about common knowledge.

What is common knowledge?

Other terms for common knowledge include open knowledge, conspicuous knowledge, public knowledge, interactive knowledge, shared reality, shared awareness, collective consciousness, and common ground.

Why is common knowledge important?

Many of our harmonies and discords, I hope to show, fall out of our struggles to achieve, sustain, or prevent common knowledge.

Later, Pinker asserts:

Many of our tensions, personal and political, arise from the desire to propagate or suppress common knowledge.

What answers does Pinker's book answer?

Pinker's book answers questions like:

- Why do people hoard toilet paper at the first sign of an emergency?

- Why are Super Bowl ads filled with ads for crypto?

- Why, in American presidential primary voting, do citizens typically select the candidate they believe is preferred by others rather than their favorite?

- Why did Russian authorities arrest a protester who carried a blank sign?

- Why is it so hard for nervous lovers to say goodbye at the end of a phone call?

- Why does everyone agree that if we were completely honest all the time, life would be unbearable?

Where Pinker disagrees with Yuval Harari

Yuval Harari and Stephen Pinker are among my top 3 authors (I also love Bill Bryson). Therefore, my ears paid attention when Pinker disagreed with a minor point Harari made about humans creating fictions. I quoted one of those fictions when I explained Why is Bitcoin Worth Anything?

Pinker says Harari is too extreme when he categorizes many human inventions as "fictions." Pinker partially agrees, but points out a nuance:

Our world is built on conventions that allow us to coordinate effectively and are self-reinforcing because they are common knowledge. Conventions like the English language, Christianity, the United States of America, the euro, and Microsoft are not exactly “fictions.” They are very real, even if they are not made out of physical stuff. Common knowledge creates nonphysical realities.

This passage sums up the book

I had long wondered why people often don’t say what they mean in so many words but veil their intentions in innuendo and doublespeak, counting on their listeners to read between the lines. The answer, I suggested, was that barefaced statements generate common knowledge but genteel euphemisms do not, and common knowledge is what ratifies or annuls social relationships.

In this book I’ll expand on that theory and show how common knowledge also explains fundamental features of societal organization, such as political power and financial markets; some of the design specs of human nature, such as laughter and tears; and countless curiosities of private and public life, such as bubbles and crashes, road rage, anonymous donations, long goodbyes, revolutions that come out of nowhere, social media shaming mobs, and academic cancel culture.

By the time you finish the book I hope you’ll be equipped to understand phenomena I never got around to explaining, such as gaslighting, Kardashian celebrity (being famous for being famous), mock outrage (“I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here”), “red lines” in international relations, and the psychological difference between “cc” and “bcc” in email etiquette.

Funny story

As usual, Pinker litters his book with humor, including comic strips. One of my favorite parts is when he tells this joke:

A defendant was on trial for murder. There was strong evidence indicating his guilt, but there was no corpse. In his closing statement, the defense attorney resorted to a trick.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” he said. “I have a surprise for you all—within one minute, the person presumed dead will walk into this courtroom.”

He looked toward the courtroom door. The jurors, stunned, all looked eagerly.

A minute passed.

Nothing happened.

Finally the lawyer said, “Actually, I made up the business about the dead man walking in. But you all looked at the door with anticipation. I therefore put it to you that there is reasonable doubt in this case as to whether anyone was killed, and I must insist that you return a verdict of ‘not guilty.’”

The jury retired to deliberate.

A few minutes later, they returned and pronounced a verdict of “guilty.”

“But how could you do that?” bellowed the lawyer. “You must have had some doubt. I saw all of you stare at the door.”

The jury foreman replied, “Oh, we looked, but your client didn’t.”

Social paradox

I learned about a social paradox, a term suggested by the psychologist David Pinsof for phenomena like these:

1. We try to gain status by not caring about status.

2. We rebel against conformity in the same way as everyone else.

3. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people.

4. We don’t care what people think, and we want them to think this.

5. We make anonymous donations to get credit for not caring about getting credit.

6. We bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us.

7. We avoid being manipulative to get people to do what we want them to do.

8. We compete to be less competitive than our rivals.

9. We help those in need, regardless of self-interest, because being seen as the type of person who helps those in need, regardless of self-interest, is in our self-interest.

10. We make subversive art that only high-status people appreciate.

11. We make fun of ourselves for being uncool to prove we’re cool.

12. We self-righteously defend false beliefs to prove we care more about the truth than virtue-signaling.

13. We help our friends without expecting anything in return, because we know they would do the same for us.

14. We show everyone our true, authentic self—not who society wants us to be—because that is who society wants us to be.

Chapter against wokeism

One of the things I admire most about Pinker is that he's a moderate, unlike most of the leftists at Harvard. Pinker spends a chapter destroying the woke ideology and the cancel culture, which is contrary to the open discourse that universities must have. He writes:

According to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), between 2000 and mid-2024 there were more than thirteen hundred attempts to punish scholars for constitutionally protected speech in American colleges and universities. These included 243 incidents of censorship and 273 firings, 62 of them of tenured professors, a regime of intellectual repression more severe than during the McCarthy era.

Worse, for every scholar who is sanctioned, many more self-censor, knowing they could be next. It’s no better for the students, a majority of whom say that the campus climate prevents them from saying things they believe.

Academic freedom, once a narrow concern of academics, was thrust into the national spotlight in late 2023 because of a widely viewed congressional hearing on anti-Semitism on American campuses, in which legislators grilled the presidents of three of America’s eminent universities, including Harvard, my employer.

In response to the hypothetical question of whether students calling for the genocide of Jews violated university policies, Harvard’s president, Claudine Gay, gave the inadvertently Bartlett’s-worthy answer, “It depends on the context.”

The fury, from both the right and the left, was white-hot. Gay was technically correct in saying that students’ political slogans are not punishable by Harvard’s rules unless they cross over into intimidation or incitement of violence, just as they are not punishable by American law under the First Amendment. But her testimony was excoriated because Harvard had just come in at last place in FIRE’s Free Speech ranking of 248 colleges, with a perfect score of zero.

Among other things, the university had effectively driven out a biologist who said there are two sexes, persecuted an epidemiologist who had signed a conservative amicus brief on gay marriage eight years earlier, and disinvited a feminist scholar who questioned the policy of housing violent men who identify as transgender in women’s prisons. So for the president of Harvard to suddenly come out as a born-again free-speech absolutist, disapproving of what genocidaires say but defending to the death their right to say it, struck onlookers as disingenuous.

A cry for free speech

The debacle added another millstone to the sinking reputation of American higher education, a descent more precipitous than for any other institution. A major reason was the impression that universities were enforcing orthodoxies and repressing disagreement, like the inquisitions, purges, and fatwas of more benighted times and places. The impression had already been stoked by viral videos of professors being mobbed, cursed, and heckled into silence.

Conclusion

With so many good passages, why only 3.5 stars? It's because the first 100 pages are filled with tedious logic exercises that disinterested me. In all the other Pinker books, I savor every word. In When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows, I skipped pages, exhausted by Pinker's nonstop discussion about how John knows what Sally thinks about John knowing about Sally's kid (and far more layered than that!). My eyes rolled.

Still, When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows is another worthwhile book, even if it's Pinker's worst. Pinker's worst is among the top 1% of all nonfiction books of 2025.