Reviews

You won't find reviews of Hike Your Own Hike or The Hidden Europe here (that's a lie: there's one review for The Hidden Europe). Instead, this section is for my review of other books, especially nonfiction books, which I comprise 95% of my reading. I occasionally review clothes, movies, a politician, a gadget, or anything else that looks promising.

I've put my best reviews here, but if it's not enough, then you'll find hundreds of reviews on Amazon. I am one of the top 10,000 reviewers on Amazon with over 1,500 helpful votes. And yes, I can review your product if you'd like. Just contact me to see if I'm interested.

On December 5, 2017, Noam Chomsky will come out with his five millionth book. The dude is prolific. It's called Global Discontents.

The book is a collection of interviews with his loyal sympathizer David Barsamian.

I disagree with Noam Chomsky on so many issues. I often can't stand the guy.

Still, I force myself to listen to him because I respect him.

In today's echo chamber of the Internet, too many people simply surround themselves with media that reinforce their point of view. We must force ourselves to open our mind and listen to people we disagree with, even if we feel outraged.

For example, so many of my liberal San Francisco friends blame everything that's wrong in this world on Fox News. However, few have spent much time watching it. If they did, they might learn that many of the programs on Fox are as objective as any other mainstream news source.

Of course, many programs aren't, but the fact that few liberals realize that Fox News isn't always biased shows that they rarely listen to the opposition.

I pay attention to Chomsky for the same reason I watch Michael Moore's movies. I disagree with many of the points but it's important to hear their intelligent (or at least entertaining) arguments.

The day after our Jackass-In-Chief won the election I cried like a pussy and then wrote, “3 Great Things About Donald Trump’s Victory.”

It was good therapy for me and I hope it calmed down my liberal friends who had become stupidly hysterical.

Now that the Trumpster has been in office for 100 days, it’s the traditional time to judge his performance so far.

In my post-election article, I mentioned three silver linings in the Trump cloud:

- Democracy won.

- Russian-American relations may win.

- Mars may win.

Now that the first 100 days has passed, let’s review each one and consider a few other important points. I'll end with a shocking prediction.

I reviewed Dave Hall's excellent book, Winter in the Wilderness. I got a chance to have an exclusive interview with the author and ask him 8 questions. His answers are extremely useful for anyone who is interested in winter survival.

1. What's been the most uncomfortable/life-threatening situation you've ever survived in the winter? How did you do it?

Two events come to mind. In both instances, I didn’t feel that my life or the lives of anyone in our group were in imminent danger, but circumstances could have changed and easily become life-threatening.

The first happened when I was in college and leading a group into the High Peaks of the Adirondacks. We stayed in the Adirondack Loj campground under what I would call severe conditions, with temperatures hovering at 30 degrees below zero. Our plan was to summit Algonquin Peak the next day. With the wind chill, temperatures dropped to about 50 below during our hike.

We decided to tackle Wright Peak instead, with only four or five of us summiting while the rest of our party stayed below treeline. Our gear served us well, but it was evident that this was a potentially disastrous situation. On the way down, on the lee of a boulder, I removed my mittens to make an adjustment and the ache and pain in my hands was instantaneous.

The second situation occurred when my colleague, Tim Drake, and I led a group of students from the College of Environmental Science and Forestry on a winter overnight into the Labrador Hollow Unique Area. During this particular expedition, we faced a situation that until that point I had often thought about but never experienced. Conditions at the outset of our journey were ideal but soon took a harrowing turn. It began to rain, then sleet, then snow. This presented one of the most deadly winter survival situations into which I had ever been cast. Everything—and I mean everything—was wet. By nightfall, most of the students had finished their shelters, but it was

It began to rain, then sleet, then snow. This presented one of the most deadly winter survival situations into which I had ever been cast. Everything—and I mean everything—was wet. By nightfall, most of the students had finished their shelters, but it was fire that saved our asses. This is a skill that must be mastered, and it is situations like these that speak to its importance.

2. What's been your biggest winter survival error? What did you learn from it?

In truth, I have encountered few, if any, errors. I have certainly been uncomfortable at points throughout the years, but I have never exceeded my limitations—and it’s important to know what those limitations are. I try to stay dry and push myself to improve and expand on my skill set. I have always gone into winter situations prepared and with deliberate intentions. Even when I embark on a short cross-country skiing trip into the woods near my home, I bring along a knife and a lighter.

3. What's the biggest myth that people have about winter survival? (That it's freezing in a snow cave?)

In late 2016, I bought a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone on eBay from Nathan Gundlach, who claimed that it was unlocked. After buying it, he begged me to give him positive feedback on eBay before I got the phone. He claimed it's because PayPal won't release the money I sent him until either I give feedback or 3 days have passed. He wanted to buy more phones with the cash I sent him. He added, "Even if you don't like the phone, you can still bring up a case against me if you need to."

I trusted that the phone would be good and that he would work with me to fix it if it wasn't.

When my American friend brought the phone to Madagascar, I put my working SIM card (I know it was working since my Samsung Galaxy S6 was using it) into the S7. Result?

It's expected that a book about genetics and race will elicit extreme reactions. Just look at all the passionate 1-star reviews on A Troublesome Inheritance. I enjoyed reading them because they make good points. Nicolas Wade's book has flaws, which I'll tackle first.

Race may be a troublesome inheritance, but better to explore and understand its bearing on human nature and history than to pretend for reasons of political convenience that it has no evolutionary basis.

7 Problems with A Troublesome Inheritance

1. I was unconvinced by his arguments that genes played much of a role in helping the UK lead the Industrial Revolution. Had the Industrial Revolution and general global leadership happened in China, I suspect he would have written, "It was obvious that the Industrial Revolution would occur in China because East Asians evolved to have the highest IQ among all the races. It's Chinese genes, which favor high IQ, that ultimately resulted in their race/culture being the winning/dominant one on the planet."

2. I would have preferred he spend less time talking about Francis Fukuyama's analysis of the rise and fall of empires and spend more time on the latest genetic research on racial differences.

3. In the conclusion, he wimps out and gives in to the politically correct orthodoxy which he claims to defy.

For example, after spending much of the book explaining how the West (and to some extent China) have produced superior/stronger civilizations than other races/societies, then he backtracks. He says, "There is no assertion of superiority." (Loc 3761 on Kindle). And later, "All human races are variations on a common theme. There is no basis from an evolutionary perspective for declaring anyone variation superior to any other."

4. Despite being written in 2014, he never uses the word "epigenetics" in the book. This fast-moving field is critical to understanding how quickly evolution can move. It would vastly support his argument (or at least give it another dimension). However, it fails to enter his radar.

5. He becomes annoying by how often he repeats this phrase: "New analyses of the human genome establish that human evolution has been recent, copious and regional." He bangs that drum at least four times.

6. East Asian are intellectual superstars, but then why was South Korea and Taiwan equal to Ghana 60 years ago?

Why are some countries rich and others persistently poor? Capital and information flow fairly freely, so what is it that prevents poor countries from taking out a loan, copying every Scandinavian institution, and becoming as rich and peaceful as Denmark? Africa has absorbed billions of dollars in aid over the past half century and yet, until a recent spurt of growth, its standard of living has stagnated for decades. South Korea and Taiwan, on the other hand, almost as poor at the start of the period, have enjoyed an economic resurgence.

Wade will say that genes are a factor, but then why were East Asians so far behind back in 1960?

7. Wrong fact. He writes: "The homicide rate in the United States, Europe, China, and Japan is less than 2 per 100,000 people, whereas, in most African countries south of the Sahara, it exceeds 10 per 100,000, a difference that does not prove but surely allows room for a genetic contribution to greater violence in the less developed world."

First, the US homicide rate is twice as high as he claims, according to the UN.

Second, he's focusing on Africa, whereas he ought to be focused on Latin America, which has the highest homicide rate.

Third, the way to prove that genes play a role isn't to do a simple analysis like he's doing. What they need to do is to take South Americans (and Africans) out of their countries and place them in rich, peaceful countries (like Northern European ones). If, after a couple of generations, the descendants of those non-Europeans are still more violent than the mean, then you argue that genes play a role.

Everyone loves books with provocative questions as their titles. Are Racists Crazy? strikes that nerve. Now that's even better than the title of another book that I read recently: What if There Were No Whites in South Africa?

Unfortunately, Are Racists Crazy? How Prejudice, Racism, and Antisemitism Became Markers of Insanity reminds me of What if there were no whites in South Africa? It doesn't leave you with a definitive answer.

Perhaps that's my fault. I come in with expectations of having a simple YES/NO conclusion, when clearly the question is nuanced and complex, which explains why you need a book to answer it.

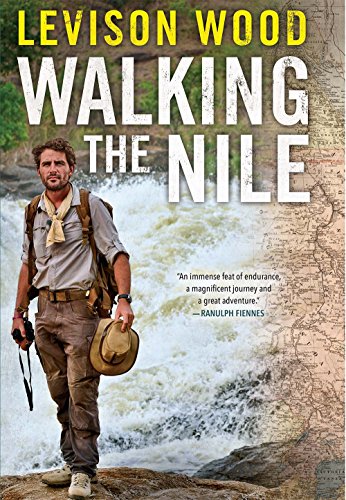

I, like Levison Wood, love to walk. I’ve hiked 25,000 kilometers the last 20 years. My longest trek was when I walked 9,000 km (5,600 miles) from Mexico to Canada and back on the rocky, mountainous, and snowy Continental Divide Trail.

In comparison, Lev Wood planned to follow the Nile downstream for its complete length of 6,800 km (4,250 miles), which is 25% shorter than the route I took and having far less elevation gain than walking the spine of America’s Rocky Mountains.

He would take 9 months, while I hiked my round-trip in 7 months.

I make this comparison not to argue that my trip was “harder” or that my wood is longer that Wood's wood. My trip was simply different than Wood’s.

The reason I make this comparison is so that you can understand my perspective when I read Walking The Nile—I’m not your average armchair travelogue reader—I have a good idea what it takes to do what he did. And it’s precisely for that reason that I both admire Lev Wood and criticize him. There are six positive traits about Walking The Nile and seven negative ones.

I've written some unorthodox views about climate change before, including my debate with a T-Rex and my suggestions on how to solve climate change. This sparked some climate change debate on my forum.

Given my interest in climate change, Oxford University Press sent me an advanced copy of Climate Change and the Health of Nations: Famines, Fevers, and the Fate of Populations by the late Anthony McMichael. In 2014, McMichael, an Australian public health researcher, died at the age of 72. His two co-authors helped complete his work, which will be published in 2017.

What's the point of the book?

The point of Climate Change and the Health of Nations is to follow the advice of historian Geoffrey Parker, who encouraged us to take the road less traveled: "We have two ways to anticipate the impact of a future catastrophic climate change . . . Either we 'fast-forward' the tape of history and predict what might happen on the basis of current trends; or we 'rewind the tape' and learn from what happened during global catastrophes in the past. Although many experts have tried the former, few have systematically attempted the latter."

In short, McMichael does what mutual fund managers always tells us not to do: to use past performance to predict future results.

Here are some of the questions that he answers (among many):

- Did climate change 23,000 years ago hasten the demise of the Neanderthals?

- How did the prolonged drying of the Sahara 5,500 years ago affect food yields?

- Did humans in southern Mesopotamia 4,000 years ago suffer due to climate change?

As you would expect, there's plenty of doom and gloom in this book. McMichael reports that "the rate of heating would be about 30 times faster than when Earth emerged from the most recent ice age, between 17,000 and 12,000 years ago." However, there are snippets of refreshing observations.

The climate has changed rapidly even when SUVs didn't exist

One of the biggest myths about our present-day climate change is that it's the first time in the history of the planet that the climate has changed as fast as it's changing now. The American Institute of Physics proves that's false.

Even McMichael recognizes this when he admits: "While the drying of the Sahara from around 6,000 years ago occurred in unhurried fashion over several centuries, regional changes in climate in the Dead Sea region in the early millennia of the Holocene led to desertification within decades."

It's moments like this that we know that McMichael doesn't have a one-sided argument. Still, he reports, "The last time the planet's temperature rose by 4 degrees was 56 million years ago, but that change occurred over thousands of years, not over a single century."

He's relatively balanced. At times, he's simply brilliant.

In 2016, Nigeria's Chibok girls have continued to dominate the news from Nigeria. In October 2016, Boko Haram released 21 girls. The NY Times reported that another 83 girls may get released soon. The NYC newspaper also says that 100 girls (of the original 270 who were abducted) may never want to return home because either they are brainwashed or ashamed to face their communities now that they are "damaged goods."

On December 5, 2016, Chibok Girls: The Boko Haram Kidnappings and Islamist Militancy in Nigeria by Helon Habila will be released. The publisher sent me an advanced copy to review.

The book is dated even before it hits the stands, since it does not capture the latest news of the release of 21 girls nor the possible 83 who may also return home. Still, it's a good 130-page overview of the situation so far.

Habila gambles by going into the lion's den. He travels to Chibok and the surrounding area to pick up first-hand knowledge of the state of affairs. For that reason, I recommend the book.

What is disappointing is the book's length. At 130 pages, it's doesn't go that much deeper than what you can gleen from reading internet articles for a couple of hours. I've been following the situation and I didn't learn much. But for someone who knows little, this is an excellent summary. Moreover, because it's a personal account, it can be riviting at times. Its anecdotes are telling. Like this one:

In Northeast Nigeria, there are signs telling drivers that it is illegal to give bribes at checkpoints, with a phone number to call if a soldier solicited for bribe. This was the face of the new government in 2015, elected with promise to wipe out corruption and Boko Haram. Abbas told me he had tried the numbers and they didn't work.

It's such a classic African story. I have several of mine own like that.

Habila is reasonable most of the time, but I strongly disagree with Habila when he writes:

"I used to wonder why the facilities at our airports and in almost all public buildings in Nigeria or always broken and sub-standard, until I realized it was not accidental. It is a way of controlling the masses. The masses must never be allowed to think they deserve standard service."

This is a terrible and silly argument. It's unproductive victimhood. The reason airports and public buildings are a disaster in most of Africa is that its leaders are incompentent and Africans just don't care that much about it.

Imagine you're the head of some African state and that you want to control the masses. What would be more effective:

a) Have pathetic buildings, screwed up roads, and crumbling airports?

b) Have infrastructure like Switzerland?

Books about South Africa are sometimes racially biased. The New Black Middle Class in South Africa is not. The author, Professor Roger Southall, writes a level-headed, dispassionate analysis of the emergent middle class in South Africa.

After spending half a year all over South Africa and having picked up over 100 hitchhikers (98% were black), I learned a lot about the racial tensions in South Africa. I saw strong parallels with the USA. Although I was born in 1970, I imagine that South Africa is where the USA was in the first 10 years after aparteid (1965-1975).

Today, even though blacks hold the political power in democratic South Africa (because just 8% of the voters are white), many still blame much of their misfortunes on whites. For instance, their dismal literacy rates of 100 years ago are often faulted on the colonial period.

Southall traces the rise of the black middle class and the force of literacy. In 1911, South Africa's first census concluded that 6.8 percent of its blacks were literate. Before we're quick to blame the white colonists for this low figure, let's remember that prior to the arrivals of the whites, no sub-Saharan society (except Ethiopia) had ever invented writing.

Throughout the 20th century, schools became more common throughout Africa. Today, 94% of South Africans are literate. This has helped fuel the rise of the middle class.

South Africa's literacy rate is much higher than other sub-Saharan countries that had far less intense colonization than South Africa. The average youth literacy rate in the sub-Sahara is just 71%. For young women in sub-Saharan Africa, the rate remains dismally low at 65%.

According to the 2016 UIS estimates, the literacy rate for young men and women is a mere 16% in Niger and below 30% in Afghanistan, Guinea, Mali, and South Sudan (only Afganistan is not in the sub-Sahara). If colonialism is to blame, then why is South Africa (having been far more colonized than those other countries) doing so much better on the education front?

In 1970, 2.7 million black children were in [South African] schools. By 1988, it was 7 million; a third of university students were black.

Today, blacks are the majority of students and the majority of the university administrators. They run the show. Still, given the ongoing 2016 university protests, the students are more dissatisfied than ever.

It's getting harder for South African students to blame the whites for their frustration, but some still do. For example, one student placed a piece of shit on the head of the statue of Cecil Rhodes. Eventually, after much protests, they removed the statue. Now everything is so much better.

- Esoteric Empathy book by Raven Digitalis

- Out of Eden book by David Barash

- How to Survive in the Wild book by Martin and Casucci

- The Planet Remade book by Oliver Morton

- Running With Rhinos book by Ed Warner

- Guide Book Review: TED Talks by Chris Anderson

- Book Review: Attractive Unattractive Americans by René Zografos

- The Shock of the Anthropocene book

- Book Review: Missoula by Jon Krakauer

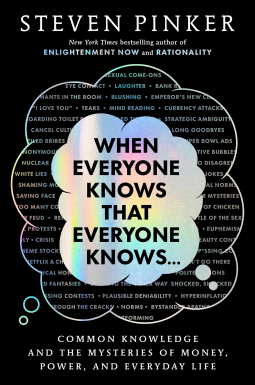

- Review of Winter in the Wilderness by Dave Hall

Your comment will be deleted if:

- It doesn't add value. (So don't just say, "Nice post!")

- You use a fake name, like "Cheap Hotels."

- You embed a self-serving link in your comment.