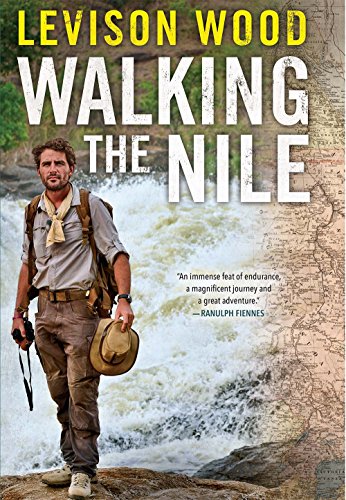

I, like Levison Wood, love to walk. I’ve hiked 25,000 kilometers the last 20 years. My longest trek was when I walked 9,000 km (5,600 miles) from Mexico to Canada and back on the rocky, mountainous, and snowy Continental Divide Trail.

In comparison, Lev Wood planned to follow the Nile downstream for its complete length of 6,800 km (4,250 miles), which is 25% shorter than the route I took and having far less elevation gain than walking the spine of America’s Rocky Mountains.

He would take 9 months, while I hiked my round-trip in 7 months.

I make this comparison not to argue that my trip was “harder” or that my wood is longer that Wood's wood. My trip was simply different than Wood’s.

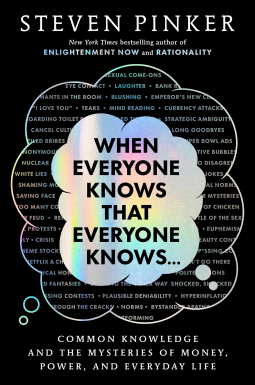

The reason I make this comparison is so that you can understand my perspective when I read Walking The Nile—I’m not your average armchair travelogue reader—I have a good idea what it takes to do what he did. And it’s precisely for that reason that I both admire Lev Wood and criticize him. There are six positive traits about Walking The Nile and seven negative ones.

The Six Positive Traits about Walking The Nile

First, let’s review the six good things about his journey.

1. Just the sheer balls Lev had to undertake such an audacious journey is remarkable. Lev Wood gets my profound respect for that.

2. His aiming for purity. He could have easily started his journey in northern Lake Victoria, which most people say is the source of the Nile. Instead, Lev wanted to preempt potential critics by starting at the furthest known Nile source, which he believes trickles out of Rwanda’s Nyungwe rainforest. It’s from there that a trickle of water becomes the Mbirurumbe river, which then merges with the Nyaborongo river, then the Kagera, which ultimately dumps into Lake Victoria. However, Burundi has the southernmost source of the Nile. So did he pick the wrong starting point? He doesn't talk about why he thinks Burundi isn't the best starting point even though it's the southernmost Nile source.

3. I also love that he instituted some pretty strict rules for his trek. For example, just like Ed Stafford (who walked the length of the Amazon), Wood wouldn’t allow himself to use the river to make a forward progress. He could cross the river, but he would have to get back to where he started. He also stated that he would always be next to the river whenever possible. Some sections are swampy, so he would obviously have to keep his distance.

4. Wood’s courage. When Lev went in 2014, South Sudan was in the middle of a civil war, where a couple of hundred kilometers of the Sudd (a swampy section of the Nile that had thwarted many explorers of yesteryear), was under rebel control. Despite this obvious impediment, he embarked on this journey anyway with the hope that he would overcome that obstacle when he got there.

5. Excitement. Long walks can often be monotonous and uneventful. Hence, I expected a dull book that described kilometer after kilometer of a slow, dull slog downstream. I was wrong. There are plenty of exciting moments. At one point, two of his guides plot to tie him up and steal from him. At another, Matt Power, a journalist who planned to cover the story by walking a week with Wood, died of heatstroke in Wood’s arms. In South Sudan, there were firefights nearby him as he stayed in a semi-destroyed hotel. In Egypt, authorities arrested him. At another point, an Egyptian mob almost turned on him. None of these dramatic moments felt exaggerated or contrived (which other authors sometimes do). They felt genuinely authentic, scary, and tense. It made for an engaging book.

6. He often takes a break from the hiking narrative to share the history of the places he is walking through. This makes the book informative and provides useful breaks from the walking tale.

Memorable Quotations

The book has a few passages that are worth sharing:

“If there’s one thing you should learn in Africa, it’s don’t lend money.” -- Ndoole Boston, a Congolese living in Uganda, guide for the Lev Wood expedition

It’s a myth that camels can go on for weeks without water. When it’s hard, they struggle to survive for more than four days.

“There is nothing more problematic in Africa than a border crossing.” – Levison Wood

When an Egyptian major asked Lev for his permission, Lev wrote, “I had faced this question countless times before. In Uganda, I had fought it with officiousness of my own; in Sudan, with humility and respect. Here, I would have to play the hapless tourist if I wanted to find a way through.” However, that strategy didn’t work as they confiscated all this camera equipment and gear. That’s when he admitted that his “hapless-tourist act wasn’t working.” He started demanding the name of all the officers and claimed that he knew a General Mostafa Yousry who would get them all fired. That worked and they returned his gear.

Nub means gold. Hence, Nubia is the city of gold.

Seven Criticisms of Levison Wood’s Walk

It’s easy to criticize Wood using 20/20 hindsight, so I will. Of course, I’m sure he would have done many things differently too, so he might agree with my criticisms.

It’s easy to criticize Wood using 20/20 hindsight, so I will. Of course, I’m sure he would have done many things differently too, so he might agree with my criticisms.

1. Wood’s timing was odd. He started in late November 2013 in Rwanda. The only apparent reason for such a start date was that Wood wanted to get through the swampy Sudd before the rainy season made it “impassable.”

I don’t understand Wood’s logic. It seems to me that all the rainy season would do would be to make the borders of this swampy section of the Nile expand. That doesn’t make that section impassable, but rather it makes it become a pain-in-the-ass to circumvent.

The swelling of the swampland would simply extend the journey as they would have to walk on land around its enlarged perimeter. Although this would be time-consuming, there must be villages (and trails) all along this perimeter, since such annual swelling occurred for centuries. Locals would have settled in places that were safe from the annual flooding. Aside from the rebel activity in Sudd (which would have been their headquarters whether it was the rainy season or not), why couldn’t Wood have simply given the swamp wide berth during the rainy season? He never addresses that.

“Who cares?” you may ask.

His odd timing resulted in Wood walking through much of the Nile in the hottest time of the year. This contributed to the heatstroke-induced death of Matt Power. It also resulted in Wood’s numerous blisters, discomfort, and thirst.

He finished his trek August 30, 2014, in Alexandria, Egypt. This is the most brutally hot period of the year. Indeed, from March to October, the northern part of Africa is extremely hot. I solo hiked to the top of the tallest mountain of Niger during the hottest time of year—so I know how it feels to exert yourself in such heat. An ice bucket challenge would be a pleasure.

Since Wood started in Rwanda, it doesn’t really matter (temperature-wise) what time of year you start, since the equatorial temperature doesn’t vary as dramatically throughout the year as it does in the north.

Therefore, he should have started in April or May, when temperatures in Rwanda are about the same temperature as they are in December. Perhaps that would have put him into the swampy Sudd during the rainy season and extended his trip by a couple of weeks. However, by starting in April-May, he would have walked through Sudan as temperatures started to cool (in September). This also means that his nine-month walk would have ended in Egypt when it’s nice and cool.

Instead, Wood inexplicably started in late November, so that temperatures got more and more hot as he progressed rather than cooler and cooler. He never explains his timing, nor does he seem to regret his timing (other than him whining about the heat and its effects).

2. Wood skipped ahead—twice! The first time Lev skipped ahead was when he reached the Sudd (due to warfare). He flew to Sudan’s capital (Khartoum) and then walked south in an attempt to cover the Sudd, but he came up short and left hundreds of kilometers un-walked.

The second time he skipped ahead was at the Aswan Dam (due to Egyptian bureaucracy). Fortunately, he did walk back to complete the skipped miles.

Wood admires the explorers of old so much, yet those explorers never had the luxury of getting on a plane (or a car) and skipping ahead. The elegance of Lev’s journey was corrupted.

In the long-distance trails such skips are called “flip-flops.” I’m fine with them. If someone flip flops the Appalachian Trail, I’d still agree that she thru-hiked the AT. However, if she’s trying to set a record of some kind, she ought to hike the trail continuously in one direction. The more ambitious the goal, the more strict should be the requirements.

3. Wood never returned to complete the Sudd. This is my biggest objection because it invalidates his claim that he “walked the whole Nile.” Some might forgive him, especially since he went the extra kilometer to do the Rwanda section, but a purist wouldn’t.

Wood admits his failure of being unable to walk the complete Nile: “The Sudd had beaten me” (Loc 2556, in the Kindle edition). Later, he reiterates his failure: “It is widely believed that the Sudd defeated [the Roman explorers], just as it defeated me” (Loc 2942). A few times he admits that his trek is now “broken.” He concludes, the Nile “had ultimately defeated me, like it had so many others” (Loc 3930).

The bottom line is that there’s a gap of a couple of hundred kilometers that he never walked. However, at the end Walking The Nile, he writes, “There was nowhere left to walk.”

Of course there is! Go back and do the Sudd section, dude!

4. Wood took shortcuts in Egypt. After skipping the Sudd swamp, Wood seems to have lost his purity ethic. In southern Egypt, the Nile twists and turns like a snake. There are places where it makes horseshoe turns. If you strictly hug its banks, you’ll end up walking far more distance (and taking far more time) than if you took some shortcuts.

I wouldn’t mind if he shaved off a kilometer here and there. However, he created a massive bypass that would take him far from the Nile for several days. How far? Wood figured that he would “never be more than 40 km away from the river.” He also figured that if their water supply ever gets low, “we will head for the river.” (Loc 3076).

Dude, weren’t you supposed to be walking the Nile? The one problem you should never have when you walk the Nile is a lack of water!

Nothing was forcing him to stay so far away from the Nile. Yes, he had some time pressure from the Egyptian authorities, but he also spent four days taking it easy in Cairo, so he wasn’t in that big of a rush.

Besides losing the purity of walking along the Nile’s banks, this shortcut ended up endangering Wood, his guides, and his load-carrying camels. The men nearly collapsed from dehydration. When they walked back to the Nile, he recalled, “The sight of the distant Nile was like a mirage, appearing on the horizon as a ribbon of emerald green.” So much for walking next to the Nile. Fail.

Had he stayed on the Nile’s bank, he wouldn’t have had to carry so much water nor endanger himself and his crew. So many times in the book he says that he regrets Matt Power’s death and that he vowed to take all precautions from that ever happening again.

When his Egyptian guides admitted that they didn’t know if there was an oasis along the shortcut that they planned to take, Lev could have ordered the team to hug the Nile. Instead, Lev put everyone at risk and took a shortcut that also undermined the purity of his mission.

“I’m glad I’m not walking around this [Aswan dam], I thought, bitterly. To hell with the rules of this broken expedition.” – Levison Wood, Loc 3383

5. Wood spent $34,000 to walk across Egypt. That’s not a typo. He repeated that figure multiple times, partly because he was also shocked and embarrassed by the amount. He wrote:

“That sort of money would not only break the bank, but it would max out my credit, bring a tear to the eye of my sponsors, and bring into question the entire ethics of the expedition. But if I didn’t pay, then the past seven months of walking, and several years of planning, would be a complete waste of time. There’d be no film, no book, and no money to give to the charities I’d wanted to support. In effect, it was pay or give up.”

I understand his logic and I’ve never been to Egypt, so it’s hard for me to criticize this issue too much. On the other hand, I’ve been to 44 out of 54 African countries, entering all of them overland in a car (which is more complicated than doing it on foot). I’ve climbed the tallest peak in every African country that I’ve visited. I’ve had to bribe many Africans along the way. However, never have I had to spend more than $100 on any bribe. This $34,000 bribe is truly astronomical and sets off all sorts of red flags.

When Lev asked Turbo (his Egyptian guide/fixer) if the $34,000 went to waste, “Turbo smiled. ‘Nope! It’s all good.’ I knew what that smile meant: it had taken every penny to pay my minders, guides, and expenses; and he had had to move heaven and earth to get the police, army, security service, Ministries of Information, Tourism, Antiquities and Border on the side.”

No, Lev, that’s not why Turbo was smiling. He was smiling because he’s thrilled that you’re such a sucker since he probably pocketed around $20,000. An Egyptian taxi driver won’t make that kind of money in one year, let alone in 45 days.

Let’s budget $4,000 for the renting a car for 45 days, including a driver and petrol. Where did the other $30,000 go? Perhaps $5,000 went for the police officers who were to escort/tail/protect Lev for 45 days. At most, a few thousand dollars went for bribes. The rest ($20K+) went into Turbo’s pocket.

I’m not suggesting that Lev pocketed the money and just billed his sponsors. However, I am suggesting that he’s an absolutely atrocious negotiator. For starters, he didn’t even try to reduce the price. When the guy on the phone told him, “For you, I’ll give you a special price of just $34,000,” Lev didn’t even try to counter with, “How about $5,000? Or $10,000?” He didn’t even try to get it down to $30,000!

In my African experience, most negotiations end at half the opening bid. This suggests that Lev could have gotten the deal done for $17,000.

He probably would have bargained harder if (a) he didn’t have money; (b) his sponsors weren’t footing some or all of the bill.

He could have just positioned himself as a poor guy and said, “Look! I can’t even afford a car or to even take public transport! That’s why I’m walking! I’m that poor! For $34,000, I could fly around the world multiple times or buy a couple of cars!”

Instead, he just paid it without asking for even a $1 discount. How disappointing. When I go to Egypt in late 2017, it’s people like Lev would have contributed to raising the bribe price for the rest of us. Thanks, Lev.

BTW, Lev writes that the Aswan High Dam is the “biggest in the world” (Loc 3383). Five years before he did his trek, China’s Three Gorges Dam was already the world’s biggest dam.

6. Wood often didn’t carry his own backpack. This is a minor issue, but a modern purist wouldn’t have used so many porters. However, Wood fashions himself as an explorer like his nineteenth-century heroes (Burton, Speke, etc.). Perhaps that’s why he’s unashamed to have a team of porters.

Indeed, it’s only in a short section of Egypt where he ever feels alone. And even then he’s not truly alone since Turbo (his Egyptian guide) is always relatively close to his car further up the road. His car is filled with food and refreshments.

“Turbo was never far away, and always on the end of the satellite phone, but this was the first time in the trek I’d felt truly alone: no Boston [his first guide], nor Moez [another guide], nor any porters constantly chirping in my ear.”

7. Wood could have gone faster. This is also a minor point. In Egypt, for example, he said “it would not be easy” to cover 37 kilometers (23 miles) a day.

Many seasoned thru-hikers easily do that while going up and down mountains all day and carrying four days of food, shelter, and water in their backpacks. Lev was carrying little most of the time and he was mostly walking on a slight downhill slope. Had he picked up the pace of the whole journey, he could have fit more of it in the cool season and paid a smaller bribe since the police would only have to escort him for 20 days instead of 45.

Conclusion

Walking the Nile is an excellent book for those who enjoy adventurous travelogues of remarkable journeys. What Lev Wood did is absolutely incredible and commendable.

Let’s be clear: I’m certainly not criticizing Lev for skipping the Sudd. Had he not skipped it, it’s quite possible that he would have been killed or kidnapped. Skipping it was the right thing to do.

Moreover, my nitpicking about his pace, his use of porters, and paying $34,000 to walk across Egypt is simply that: nitpicking. You could accuse me of being petty. That’s fair, which is why I don’t want to make a big deal about such things.

My main objection is that despite skipping the Sudd, he claims that he walked the whole Nile. I could even have tolerated his flip-flopping. However, he hosted a 4-part British TV show about his Nile walk, did many TV interviews, and has implied in all his publicity that he “walked the entire Nile.”

If I claimed to have run a two-hour marathon (which has never been done before) and then, in a footnote, I admit that I skipped one of the 42 kilometers, wouldn’t my claim be false?

Lev needed to simply say, “I almost walked the entire Nile.”

Of course, that’s less satisfying and fails to get attention. It’s similar to when another British adventurer, Arctic explorer Ben Saunders, who took two similar shortcuts in his epic journeys but didn’t let those shortcuts affect his marketing message. First, he claimed to have walked to the North Pole, but the helicopter dropped him off over 60 kilometers from the nearest Russian island (thereby skipping the proper starting point). He had good reasons to skip, but this broke the journey’s purism. Second, in Saunders’s “unsupported” trek across Antarctica, he got an airdrop at the end as he ran out of food. Fail.

As Carl Sagan said, “Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.”

I commend Wood and Saunders for being honest about their shortcomings. I just wish their marketing claims and messages would be equally forthright.

Lev would say that he never explicitly claims that he walked every kilometer of the Nile. That’s true. If you read the book blurb and his website like a lawyer, you’ll see that he never makes such a claim. Instead, his marketing trumpets that “Lev set forth on foot, aiming to become the first person to walk the entire length of the Nile” or “Lev completed a nine-month expedition walking the length of the Nile.”

Neither of those statements is an outright lie, but they both imply that Lev did something that he didn’t. At speaking events, I doubt that Lev ever corrects his hosts when they declare, “So everyone please welcome Lev Wood, the first person to walk the entire Nile!”

Truly frustrating

Perhaps what’s most frustrating about Lev’s walk is that it discourages future adventurers from truly walking the Nile. Imagine if, in 2025, a Russian completes the walk that Lev envisioned, including the elusive Sudd section. What would happen? The Western media will all say, “Yeah, but a Brit already walked the Nile, so Mr. Russian, stop saying that you’re the first to do it.”

“But,” the Russian would insist, “Lev skipped the Sudd!”

“Oh come on! Are you really going to nitpick that? C’mon, he basically did the whole thing! There was a civil war going on in the Sudd when our boy Lev was hiking through! Cut him some slack! Just be happy that you’re in second place, Russian boy!”

Sympathy

I sympathize with Lev. I also mislead people about my hiking accomplishments. For example, I regularly claim that I’ve walked across America four times and walked across Spain twice. Since the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail isn’t at the Candian border and the AT’s southern terminus isn’t at the ocean, you can’t really claim that you walked across America when you do the AT.

Moreover, crossword puzzle aficionados will object when you say that you hiked “across America,” as they will envision an east-west journey, not a north-south one. For the same reason, some critics might say that walking from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic via the Pyrenees shouldn’t count as walking across Spain (since that’s a south-to-north traverse).

However, saying that “I walked across America 3.7 times on a north-south axis and I hiked across Spain once from north-to-south and the other time east-to-west on El Camino de Santiago” will simply confuse people. It’s just easier to say, “I walked across America 4 times and Spain twice.”

For Lev, being accurate wouldn’t be such a mouthful. He could simply say, “I walked nearly the entire Nile.”

There. That’s short.

But that’s not sexy. Lev’s sponsors would be disappointed. He would fail to make headlines and sell books. So instead, Lev has chosen to subtly mislead. And that’s one reason why I give his book 3 stars.

Had his marketing been more forthright and he'd changed a few other things that I mentioned above, then I’d give it 8/10.

VERDICT: 3 stars