Reviews

You won't find reviews of Hike Your Own Hike or The Hidden Europe here (that's a lie: there's one review for The Hidden Europe). Instead, this section is for my review of other books, especially nonfiction books, which I comprise 95% of my reading. I occasionally review clothes, movies, a politician, a gadget, or anything else that looks promising.

I've put my best reviews here, but if it's not enough, then you'll find hundreds of reviews on Amazon. I am one of the top 10,000 reviewers on Amazon with over 1,500 helpful votes. And yes, I can review your product if you'd like. Just contact me to see if I'm interested.

I've tried mushrooms twice in my life. Once was in Amsterdam. It produced a 4-hour laughing attack. It was great fun! Everything was hilarious!

The second time was at Burning Man. I expected a repeat of my Amsterdam experience but instead was treated to a 4-hour trip of extreme empathy. It was bizarre and deeply revealing.

We all like to think of ourselves as pretty good people. I certainly always pretended to give a shit about my fellow human. However, it wasn't until I took those mushrooms at Burning Man that I realized just how much more empathic I can be. I realized that I am far more disconnected that I was willing to admit to myself.

That's why when I was offered an advanced copy of Esoteric Empathy: A Magickal & Metaphysical Guide to Emotional Sensitivity by Raven Digitalis, I was interested in digging deeper into this important subject.

The book was released on December 8, 2016, which happens to be the 36-year anniversary of the death of an extremely emphatic man: John Lennon. The book's release probably is also meant to encourage people to gift a book about empathy to someone for the holidays. So should you buy it for yourself or someone else this Christmas?

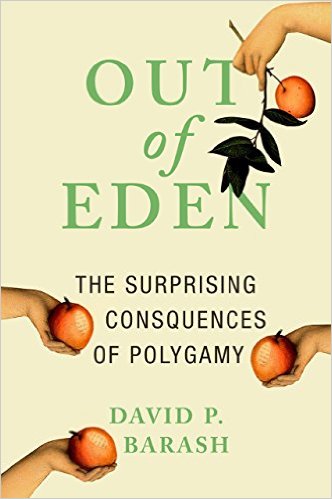

David Barash's Out of Eden examines the prevalence of polygamy in humans (it's more common than you think) and other species. First, he has to define the terms. Have you ever heard of the first term of the three below?

David Barash's Out of Eden examines the prevalence of polygamy in humans (it's more common than you think) and other species. First, he has to define the terms. Have you ever heard of the first term of the three below?

- Polygyny: When a man has more than one wife.

- Polyandry: When a woman has more than one husband.

- Polygamy: When a human has more than one spouse. Because polyandry is extremely rare, polygamy is usually synonymous with polygyny.

Right from the beginning, he recognizes that this is a touchy subject.

The biological reality is that we were "made for monogamy," despite the preferences of straight-laced (and often hypocritical) preachers, and not for free-spirited sexual adventurism either, despite the fervent desire of those seeking to justify a chosen "swinging" lifestyle.

Barash has company in the scientific community when he states that humans have polygamous tendencies. Primatologist Alan Dixson wrote a book about primate mating systems and concluded, "It is likely that Homo sapiens evolved from a primarily polygynous nonhuman primate precursor, and that the earliest members of the genus Homo were to some degree polygynous."

The esteemed Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson also agreed that humans were "moderately polygynous."

At the start of the book, Barash insists that he's not trying to promote any particular way of life. He's all about science, not morals. Still, at the end of the book, he can't help himself and injects a bit of his morality. He says that while we tend to polygamy biologically, that doesn't make it right. Barash (rightfully) criticizes those who value anything that is "natural." Sometimes natural things are bad. Some natural plants are poisonous; we have "natural" tendencies to kill each other.

Out of Eden points to various smoking guns that testify to our polygamous nature:

- Lopsided male vs. female violence ratio: Men commit 10 times more violent crimes than women. It's a classic sign of polygamy in the animal kingdom. Male-on-male violence is at least 20 times more common than female-on-female violence. Such patterns hold throughout recorded history.

- Female sexual maturity is earlier than men. "In all polygynous species, females become sexually and socially mature at a younger age than do males."

- Native American tribes: "Nearly all the Indian tribes of North and South America are polygamous.

- Nearly all societies punish female infidelity more. "The patriarchal 'double standard' is pretty much a cross-cultural universal. Once again, this is because female infidelity raises the possibility of a man rearing another's children, whereas its male counterpart--for all the problems it may cause to the relationship--doesn't necessitate a comparable cost of cuckoldry."

Barash bashes the politically correct crowd that argues that girls and boys would be identical if it weren't for social conditioning and pressure. "It is downright dreary to have the same basic, male chauvinist distinctions between men and women, boys and girls, confirmed in study after study, starting in very young childhood, but there's no way around it."

Out of Eden observes: "Another cross-cultural universal: although both girls and boys typically undergo initiation rituals, these rites of passage are consistently more severe for the sperm-makers."

Speaking of violence, men are far more likely to carry the SRY gene. So what?

[The SRY gene] dooms its carriers to shorter lifespans, greater probability of death due to "accidents," as well as increased risk of being not only violent but also the victim of violence. The impact of this gene is such that substantially more than one-half of people who have run afoul of the law and are currently incarcerated carry it.

Some think polygynous male lions are terrible when they take over a pride since they kill young males. However, even God in the Holy Bible instructs his followers to do the same: "Now therefore kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman who has known man lying with him. But all the young girls who have not known man lying with him, keep alive for yourselves." (Numbers 31:17-18)

God wasn't just for polygamy, He's also a polygamous Himself! In Ezekiel 23, God is said to have two women (Samaria and Jerusalem). They are cities, but it's a symbol of bigamy.

"In addition," Out of Eden notes, "There are scores of patriarchs in the Old Testament who were polygamous." Yes, even Abraham, Esau, and Gideon had more than one wife. King Solomon had 700 wives and 300 concubines (1 Kings 11:1-3).

Koranic law limits Muslims to four wives, while the West African King of Ashanti had to be content with no more than 3,333 wives. Tough life.

Pan-African polygamous traits

One Pan-African trait I've noticed isn't just that polygamy exists in every African country and that men must always pay a bride price.

Not only that, but they typically have the right to return their purchase if it proves unacceptable; for example, if the bride isn't a virgin, doesn't conceive children, etc. A careful review of more than 200 different societies concluded that almost universally, husbands and their families show particular concern about the fertility of wives, with '"barrenness" being a predictable grievance.

Out of Eden argues that men fight to obtain the most resources in polygamous societies. The more they have, the more wives they have because wives are attracted to men with resources. The more wives they have, the more children they have. But what about African societies that are resource-poor?

Kalahari Bushmen, who inhabit a stringently resource-limited environment and are primarily monogamous as a result (in such circumstances it is difficult for a man to accumulate substantially more of anything than his fellows), 5% of the men nonethless manage to have two wives. In this and other cases, male success is less influenced by aggressiveness or violence than by ability to obtain resources which, in turn, are appealing to women: e.g., being a proficient hunter. In such cases, the proximate lure may well be the prospect of regular, nourishing meals, while the ultimate payoff is likely to be reproductive.

The doggone Dogons

Anthropologist Beverly Strassman has done for the Dogon people something they haven’t done for themselves: document their male-female relations. Dogon society is all about the man. It’s patriarchal (men hold the social, economic, and political power). It’s patrilocal (the wives must move into the man’s house, which is a common Pan-African trait). It’s patrilineal (sons inherit everything; the daughters get nothing).

During menstruation, the Dogon must move to a special hut, where she’s closely monitored. Dogons circumcise their women to theoretically decrease their sexual pleasure and appetite and thereby increase the likelihood of fidelity.

What’s the reward for Dogon women who make all these sacrifices?

Crappy husbands.

David Barash notes in Out of Eden:

[Dogon men] aren’t very dutiful fathers, spending most of their time and energy in the mating effort. They seek to enhance and maintain their social status, and with it, opportunities for more wives and thus, more children to be ignored. And so, child mortality is terribly high, with nearly one-half dying before reaching five years of age. Moreover, a Dogon child living in a polygamous family is seven to eleven times more likely to die early than if she or he is born to a monogamously mated woman. This appears due to the crucial reality that with monogamy, a woman’s success is also her husband’s, and ditto for losses. Polygamous males, on the other hand, are evolutionarily rewarded for emphasizing quantity over quality: a ‘father’ with three wives, each of whom suffers about a 50% probability of losing her child, still ends up with 1.5 children on average, compared to a monogamously mated man, who even assuming zero mortality among his offspring, ends up with only 1.0.

Like most polygynous societies, co-wives have a hierarchy. “Nearly always, the senior wife is more powerful and thus better served by polygyny than the younger, subsequent wives. It is therefore possible that at least some harem-dwelling women aren’t necessarily worse off as the reigning male acquires additional mates.”

After having talked with hundreds of female Africans, they’d disagree. They would say they become worse off even if they are the first wife. That’s because polygyny is essentially a zero-sum game: the pie is fixed, so any additional wives simply make each slice smaller.

Yes, a new wife can help contribute to babysitting and other domestic chores, but what the husband brings home matters. And it’s unlikely that he will be able to bring much more if he acquires another wife. He’ll still have the same job. It’s unlikely he’ll get promoted just because he got a second or fourth wife. Even in the old days, it was unlikely that a man would catch more meat if he got another wife.

Out of Eden points out another impact of Malian polygamy: “It isn’t clear precisely why the children of Dogon co-wives suffer such high mortality, although it is widely claimed—among Dogon women themselves—that they are often poisoned by other co-wives.”

Polygamy in Sierra Leone

Among the Mende people of Sierra Leone, for example, monogamously married women produced more children than did polygynous co-wives, on average. However, within these polygynous mateships, the most senior wives not only had greater reproductive success than their junior compatriots, but more than monogamously mated women. Since there is a dominance hierarchy among females, it may only be the ‘junior wives’ who suffer, and who might do better if they were monogamously mated.

He continues:

Out of a sample of 246 married men among the Temne people of Sierra Leone, 133 were polygynist, who were more ‘fit’ (that is, more surviving children per man) than were monogamous men. Not only that, but their ‘fitness’ increased with corresponding increases in harem size. Temne women, however, were a different story. One-quarter of the children born to monogamously mated women failed to survive infancy, whereas among bigamously mated women, infant mortality was a whopping 41%.

Polygamy in Kenya

Another example: among the Kipsigis people of Kenya, the number of surviving children declined with the number of co-wives. Thus, a monogamously married Kipsigis woman had, on average, 7.05 surviving children; a bigamously married woman, 6.82, whereas women with two or three other co-wives had 5.58 and 5.81, respectively.

In short, when a man decides to take a second wife, this is nearly always bad news for the first one. She will have to share resources and almost certainly compete with the new—and likely younger—wife and her eventual children.

Other convincing data polygynously mated women in the Sub-Sahara suffer more than those who are monogamously mated: more mental illness, especially depression, and more physical abuse.

In addition, their children fare worse by most measures. The situation is typically most challenging for junior wives, who are more likely to have lower reproductive success because their infants suffer higher mortality rates.

Polygamy in Nigeria

Monogamous Nigerian Ibo wives “actually encourage their husbands to take an additional wife, the claim being that it is not only lonely to be an ‘only wife,’ but humiliating as well, since it suggests that one’s husband isn’t very successful or otherwise desirable.

"It is also possible that even though Dogon women are reproductively ill-served by polygyny (in terms of their success in rearing offspring), they recoup these losses via enhanced numbers of grandchildren if their sons are more likely to become successful polygynists; another case of greater reproductive success by ‘sexy sons.’”

Money and Marriage

“Women are particularly likely to end up with men who are especially high status and wealthy.”

Evolutionary anthropologist John Hartung used G. P. Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (covering 1,170 societies) and the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (186 societies) to conclude that sons generally receive more inheritance than daughters.

Out of Eden explains the logic: “This preferential investment in sons, particularly on the part of upper-class families, isn’t only reflected in patterns of inheritance. In the great majority of human societies, wives are essentially purchased by the groom’s family, who, in doing so, are investing in their sons, and thereby, in their own eventual grandchildren.”

Those two ethnographic reference books also indicate that brideprice occurs in 52 to 66 percent of human societies. Dowry payment occurs in only a few East Asian societies and southern Europe.

Africans who marry up

[The Mukogodo people of Kenya] have long occupied pretty much the bottom rungs of their geographic region with regard to wealth and prestige. As a result, their reproductive opportunities are comparably limited, even though there is considerable interbreeding between the Mukogodo and neighboring groups. The problem for the Mukogodo is that their neighbors regularly out-compete Mukogodo men for wives, having more goats, sheep, and cattle to offer as bride price. As a result, the Mukogodo place substantially less value on their sons—whose breeding options are limited—than on their daughters, who have a real prospect of marrying up. Mukogodo girls receive better medical care than their brothers, and their survival (at least to age five) is higher.

The sex ratio of live births favors girls as well, suggesting—but not proving—that, in this case, infant boys may be the disproportionate victims of infanticide.

When analyzing the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, a team of anthropologists concluded that sexual and emotional conflicts among co-wives happen more than 90 percent of the time; only one in four have a “close friendship” with a co-wife.

It takes a village

Anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Hrdy’s book, Mothers and Others, persuasively argues that bi-parental care is less natural than “allo-parenting,” where the extended family also helps to raise the child. “Multi-adult allo-parenting would seem to free dominant and powerful men even more to be polygynists,” concludes David Barash.

We’ve already noted that modern Western societies that are formally monogamous turn out to be effectively polygamous, especially when considering remarriages and the formation of second and third families. There is a substantial gender asymmetry: men remarry more than do women, and have more children in their subsequent marriages. This is due to the fact that by the time of a second or third marriage, the participants are older and fertility declines dramatically with age among women but not among men.

Is polygamy good for women?

Despite the drawbacks of being a co-wife, “polygyny is actually a better deal for women than for most men. Thus, under polygyny all women get mates (at least in theory) compared with only a very small proportion of men; monogamy is therefore an equalizing and democratizing system, for men, in that it immensely increases the likelihood that they, too, will be able to marry [and reproduce].”

3 Tidbits

A study of 58 different human societies found that divorce rates tend to peak at about four years after the birth of a child, suggesting that the primary function of monogamous unions is to get child-rearing off to a good start, after which the parents are inclined to start over.

The frequency of marriages in which the husband is not the genetic father of the mother’s children ranges from 0.03 to 11.8 percent.

Women get punished much more for infidelity than men. “Indeed, such attitudes extend back to the Egyptians, Hebrews, Babylonians, Romans, Spartans, etc., who defined adultery strictly by the marital status of the woman. If no man is ‘wronged,’ then essentially, no wrong is supposed to have been done."

Conclusion

As you can see, I took copious notes. I plan to quote from Out of Eden often for my future book, The Unseen Africa. There's much more to Out of Eden that I have discussed. I especially like his examples of primates and other animals. If these excerpts make you want to know more, buy the book.

VERDICT: 9 out of 10 stars.

Do we really need yet another book on how to survive in the wild?

There are hundreds of books on outdoor survival skills.

Therefore, I was quite skeptical when I received an advanced review copy of How to Survive in the Wild by Sam Martin and Christian Casucci.

Therefore, I was quite skeptical when I received an advanced review copy of How to Survive in the Wild by Sam Martin and Christian Casucci.

I've read many of books on survival. Having backpacked over 20,000 km, I have plenty of experience outdoors, and I have had a few survival situations too. I wondered and was curious to see if How to Survive in the Wild offered anything new or different that all the other books out there.

The short answer is not really.

Nevertheless, I still liked it and recommend it, especially for beginners or those who have only read one book on survival.

Pros

- Nice illustrations (e.g., showing you how to make knots, fires, shelters, etc..)

- Reminds you how to sharpen your knife and why it's important.

- Spends Chapter 2 on how to build a log cabin! That's unusual for a survival book, which typically only teaches you how to make a temporary shelter. If you want to live in Alaska for a few months, then it could be useful.

- It also shows you how to build a well and brick over! Again, it surprised me to see a long-term survival technique in this book.

- Nice index

Cons

- It's short: 140 pages. Just the basics.

- It makes the same mistake that so many survival books make: it doesn't encourage you to just hike out, which often times is the best solution. It avoids the expensive task of having a search party look for you (which puts others at risk). It reduces worry (assuming you get out sooner than you would if you set up camp for days/weeks waiting to be rescued.

I reviewed Winter in the Wilderness: A Field Guide to Primitive Survival Skills and liked it more than this one. What's better about it is that it focuses on the deadliest season: winter. The skill set that you need to survive winter will help you anywhere.

Still, if you're looking for basic emergency survival skills along with a few long-term survival skills thrown in, this book is a fine choice. It also makes for a nice gift.

VERDICT: 7 out 10 stars.

Oliver Morton, author of The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World, is a radical thinker. However, he’s level-headed too. The Planet Remade discusses the various ways to avert an ecological catastrophe.

Oliver Morton, author of The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World, is a radical thinker. However, he’s level-headed too. The Planet Remade discusses the various ways to avert an ecological catastrophe.

The book is divided into 3 parts: energies, substances, and possibilities.

The first looks at the world's natural state—documenting the vast amount of energy on the planet. For example, humans consume 15 terawatts per year. That seems like a lot. However, when you add up all the energy on the planet, you learn that there are 120,000 terawatts.

The second part examines our current state. The final section considers the potent geoengineering angles.

Morton begins by asking two questions:

1) Do the risks of climate change merit taking severe action to lessen the risk?

2) Is it tough to reduce our emissions to near zero?

He ultimately answers “yes” to both of those questions.

Morton spends the rest of The Planet Remade illustrating the scale of the problem. For example, Morton writes:

There are many reasons why deep global cuts to carbon dioxide are difficult to achieve. . . . One is that fossil fuels are built into the foundations of the industrial and economic system, which means cutting emissions is hard—especially since the costs of the cuts are concentrated on a powerful sector of the economy. The other is that cutting carbon dioxide provides no short-term benefits. Because what matters to the climate is the total amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, not the rate at which it is inherited, carbon dioxide cuts made today will have more or less no effects on climate for thirty years. History hangs over everything. This, perhaps more than anything else, is what makes climate negotiations difficult; costs people bear now lead to benefits that other people will see in the second half of the century.

He’s also well aware of Malthusians who have always been wrong. He quotes Vogt, who said long ago, “It is obvious that 50 years hence the world cannot support three billion people at any but coolie standards.”

Therefore, Morton is wise not to underestimate human ingenuity. As I argue in The Hidden Europe, We may well cram 10, 50, or even 100 billion humans on this rock. Reproducing as much as possible is the duty of life.

In addition to not underestimating human ingenuity, The Planet Remade reminds the reader that dramatic climate changes happened quickly long before the Industrial Age.

In the far south of Algeria, on a plateau of wind-carved sandstone called Tassili n’Ajjer, there is a remarkable collection of rock art—thousands of pictures of elephants, crocodiles, ostriches and gazelles, and of people living among them as happy hunters, even pastoralists. They are less than 10,000 years old. In the early-to-middle Holocene, the temperature difference between summers and winters in the northern hemisphere was greater than it is today.” This would have “pulled the West African monsoons . . . much farther north” than it today so that some Sahara rivers would empty into the Mediterranean. Lake Chad was far larger—nearly the size of the Caspian Sea and more than all of America’s Great Lakes combined. “The canoes used by the fishing people living on its shores were as large and sophisticated as those seen on the Mediterranean.

We didn’t need SUVs to see such a change. I debated such issues extensively with a dinosaur. Still, the doomsday prophet will declare, “Yeah, but now it’s happening at an unnatural rate.”

To which The Planet Remade responds: “Around 6,000 years ago, today’s desert conditions established themselves with striking speed. . . . All that was left to record the plenty that had gone before was pollen, bones and those plaintive paintings.”

Significant climate change happened in a couple of decades. Morton writes:

The suddenness of the change, some scientists think, is evidence that there was some sort of amplification at play. When the Sahara, or large parts of it, were green, the plants were not just benefiting from the wetter climate—they were helping to maintain it, by holding together the soil and pumping rainwater back to the sky through their leaves, thus encouraging convection that cooled the surface created clouds. They kept doing this even as summer temperatures fell and the monsoon shifted to the south until a dry cooling around 6,000 years ago dealt the system its death blow; the drying made life more difficult for the vegetation, which led to further drying, which killed off yet more of the plants. Patches of desert spread and merged.

The Planet Remade is refreshing because it doesn’t just say it’s all doom and gloom. He points out that global warming has a chance of turning many parts of the Sahara back into a verdant place:

In a world with a higher carbon dioxide level, and thus more water-efficient plants, this process might be reversed; various models suggest that global warming could, in time, lead to a new greening of at least parts of the Sahara. More plants would mean more water vapor, more clouds and rain, and thus more plants—the feedbacks that brought the desert about now running in reverse. . . . The vast dried basins of the desert could be refilled.

Few in the climate change debate acknowledge that we’re living in an interglacial period of a long ice age. Yes, we’re in an ice age right now, with brief (10,000-year) periods where there’s temporary warming. Since it’s been relatively warm for 10,000 years, we’re due to return to a glacial period of this ice age (which lasts around 100,000 years). A glacial period would be far more devastating to life (especially human life) than further warming. In fact, in the 1930s, some were happy that industrialization would help thwart the looming glacial period.

Arrhenius saw the effect of industrial fossil-fuel burning on the climate as largely benign. Guy Callendar, a British scientist who followed up on Arrhenius’s work in the 1930s, was happy to conclude that the use of fossil fuels would postpone the next ice age—“the return of the deadly glaciers sould be delayed indefinitely.”

It’s crucial not to misunderstand The Planet Remade. After reading this review, you might conclude that Morton is minimizing climate change or believes that geoengineering our planet will easily solve all our problems.

Absolutely not.

I’m simply quoting some interesting passages to show how balanced this book is. In a world filled with doomsday books or climate deniers, The Planet Remade is a refreshing look at the challenge.

Morton advises us that remaking the planet using geoengineering is fraught with pitfalls. But at the same time, he argues persuasively that we must consider them since we ignore them at our peril.

The only thing I disliked about it is that there was too much history—Morton ought to spend more pages looking forward rather than looking backward. Also, he gets into the weeds of detail that will overwhelm the average reader.

Still, if you want to read some innovative solutions to climate change, then The Planet Remade should be on your bookshelf.

VERDICT: 8 out of 10 stars.

I'm traveling to all 54 African countries from 2013-2018 and I’m spending about 5 weeks in each country, so Running with Rhinos interested me. I was hoping to learn amazing rhino facts that few know about and get some insight into the rhino ecosystem. However, I was disappointed.

The author, Ed Warner, promises that this book will be different than other rhino books because it’s “written by a long-term, non-professional volunteer . . . who has worked with veterinarians and biologists who care for rhinos in Africa. Few if any laymen like me have been invited to do what amounts to some of the most dangerous volunteer fieldwork around.”

The author, Ed Warner, promises that this book will be different than other rhino books because it’s “written by a long-term, non-professional volunteer . . . who has worked with veterinarians and biologists who care for rhinos in Africa. Few if any laymen like me have been invited to do what amounts to some of the most dangerous volunteer fieldwork around.”

Yes, it’s a different perspective, but a less interesting one than the alternative. Wouldn’t you rather hear from a full-time lifelong rhino expert instead of a “non-professional volunteer” who helps out a couple of weeks per year?

First the good news

I did learn a few things. For example, I learned that most rhinos live in Southern Africa: “The black rhino is solitary unless with a calf. Fewer than 5,000 rhinos remain in the wilds of Africa, with the largest populations in South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe.”

And now the bad news

Running With Rhinos is filled with macho man stuff. Warner seems to think of himself as a John Wayne cowboy in the African bush. He’s the kind of guy who would get his leg chomped on by a crocodile and he’d shrug it off as “just a flesh wound.”

He loves to exaggerate, like when he wrote in the caption of a photo showing a rocky terrain, “Yes, folks, that’s what they call a ‘road’ in Marienfluess, Namibia.”

I’ve driven all over Namibia (and over 150,000 km in Africa) and the “road” he shows in the foreground photo isn’t a road at all (not even a crappy one). It’s a completely impassible hill of rocks. In the background of the photo, you can make out a smoother, sand-filled passage, where the truck came in. But Warner wants you to believe that they drove across that rock-filled nightmare.

I’m sure Warner did plenty of rigorous off-roading, but he prefers to spin a tall tale of his daring driving experience.

Another example is when he claimed, “There was no petrol in the whole country that year.” That’s simply an exaggeration. Yes, Zimbabwe experienced a severe petrol shortage that perhaps made people feel that there was no petrol, but there was petrol because the black market works.

He indulges in making humble brags. For example, there's the story of when he captures a snake. It’s an impressive feat, but the way he retells it is that annoying ah-shucks style. The black Africans were awed with his snake capturing skills and he shrugs it off like, “That’s just what I do.”

At other times, he comes across as the stereotypical arrogant ugly American who doesn’t adapt to the local customs, even when he knows what they are. For example, he “met three different ministers or cabinet members and the head of National Parks. I’m sure my calling everyone by first names is dead wrong in this very socially conscious society. Trouble is, I have my own set of rules. First names first. it’s always been that way with me and always will. My friends can only hope I never run into the president or the pope. (I’ve since run into four presidents and two prime ministers. I’ve called all of them by their first names. ‘Hi Bill [Clinton], I’m Ed, and this is Jackie.’”

(Notice the name drop there, another humblebrag.)

Running With Rhinos will make statements without backing it up with more detail. I would have loved it if Warner could explain why he thinks that the US “regulatory system of trophy hunting cannot properly manage deer populations. White-tailed deer are also severely hindering the regrowth of US Midwest and eastern forests, which are in crisis due to the old-growth reaching the end of its life cycle.”

It's an important and profound statement, but he just lets it die there instead of developing it. I realize it's a book about rhinos, but a few extra sentences would have shed some light on the obscure subject.

Similarly, he calls the white-tailed deer and the Canada geese “pests,” but does little to explain why they’re “pests.” Rhinos are certainly pests for many African farms. Should we kill those too? How do we decide when an animal is a "pest"? He doesn't

address that crucial issue.

There’s a Q&A at the end of the ebook, where he also throws out a tantalizing thought that he fails to develop: “Westerners have a lot to learn from African people and the wildlife with which they live.”

Really?

Great. Like what?

He doesn’t say.

From what I know, Africans are simply copying Westerners ever since they acquired Western firearms: driving all their wildlife to extinction. It’s Western organizations that are supplying much of the funding to preserve the wilderness left in Africa. If it wasn’t for Western NGOs (like the Lowveld Rhino Trust run by Dr. Susie Ellis, which Warner is giving the “net proceeds” of Running With Rhinos to), then African wildlife would be even worse off than it is.

Indeed, later in the same interview, Warner admits that: “We cannot save Africa from bad governments. Africans must evolve forms of government that work for them. Until they do, the wildlife will remain at risk.”

Exactly.

That illustrates that his previous statement about Westerners having “a lot to learn from Africans” was simply a politically correct statement with no substance to back it up.

Moreover, Running With Rhinos completely ignores the elephant in the African room: its fast-growing population. All the conservation efforts will amount to little when Africa has 2-3 billion people. He completely avoids this massive environmental issue, which is the most important issue of all. All environmental issues improve when a region depopulates.

In conclusion, Running With Rhinos is a letdown. There are promising passages, but before Warner can develop them, he changes the subject. I would have loved to hear more about the rhino ecosystem, its life cycle, its diet, and its gestation period. Instead, the words “diet” and “gestation” don’t appear in the book.

Although they shoot rhinos often with tranquilizer guns, Warner provides scant details about them. How's the dose determined? Do they sometimes accidentally kill them with an overdose? At other times do they survive the dose and run away?

This is a harsh review. I've never heard of Ed Warner or his organization before this book. I certainly commend his remarkable dedication and contribution to helping rhinos. I just dislike this book. It feels self-published, although the book cover is outstanding. Let's hope the publisher, Greenleaf, prints a better book about Africa soon.

Lastly, Warner fills the book with banal observations that makes such as, “As soon as I lay down on the ground I saw four meteors, two nearly in tandem together, streak across the sky.”

Wow.

I’ll leave you with one more of his fascinating observations, “If I stare at the stars long enough I fall asleep.”

And if you stare at this book long enough, you’ll also fall asleep too.

VERDICT: 2 out of 10 stars.

In 2013, I gave a TEDx Talk. The good news is that it has over 50,000 views, which is unusually high for a TEDx video. The bad news is that there are a few things I would have changed if I had been able to read Chris Anderson's new TED Talks book. It is "The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking." I received a free advance reading copy to review.

It's hard for me to review Attractive Unattractive Americans: How the world sees America

It's hard for me to review Attractive Unattractive Americans: How the world sees America because I'm torn.

Background on me

I've been to 100 countries and I speak 6 languages, so I'm quite familiar with what the world thinks about America. Moreover, I have three passports (USA, Chile, and France). My parents were American immigrants, I went to a French school for 10 years, I grew up speaking Spanish, and I've lived abroad for many years. As a 1st generation American, I am less attached to the US than most Americans - so I can see it a bit more objectively than most, almost like a dispassionate foreigner, which is what Zografos is.

Lastly, I've written The Hidden Europe: What Eastern Europeans Can Teach Us, which is 750 pages of what Eastern Europeans can teach us Americans. In it, I discuss what Eastern Europeans think about Americans, which makes me quite familiar with this complex subject. Currently, I'm writing a book my travels to all 54 African countries - and I'm sharing some of their thoughts about America there too.

Most importantly, I have a lot of sympathy for René Zografos, because I'm just like him: I've written books that cover generalities and stereotypes about other countries. I had to write about how the Polish, Romanians, and Russians really are like. I explained the differences between Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. It's hard to write such books, because if it's easy to either say incorrect generalities (which is what bold people do) or say nothing meaningful (which is what politically correct people do). It's a thankless task that is guaranteed to provoke endless disagreement. Therefore, I feel quite guilty and hypocritical about disagreeing with this book. But first.....

What I liked about Attractive Unattractive Americans

+ It covers every possible opinion. You hear voices from all over the spectrum. No stone is left unturned.

+ It's good toilet-seat reading. Pick it up, read 1-2 pages, put it down. You can do that easily. You can also skip around without any problems.

What I disliked about Attractive Unattractive Americans

Two French authors, Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, take you on a historical journey that shows how humans altered the planet. Their 2016 book, The Shock of the Anthropocene, is disappointing, despite the excellent translation by David Fernbach.

Around 11,500 years ago, Earth entered an interglacial period during an ice age that lasted 2.5 million years. Interglacial periods last roughly 10,000 years, so we're due for another glacial period. Instead, the planet is warming.

Welcome to the Anthropocene.

In Greek, antropos means human being, while kainos means recent; hence, we're in the Age of Humans.

The Anthropocene began in 1784 when James Watt patented the steam engine that signaled the start of the Industrial Revolution.

The Shock of the Anthropocene documents some of the events since the start of the Anthropocene:

⦁ Carbon dioxide has increased 43% - from 280 parts per million to 400 ppm.

⦁ Methane has gone up 150%.

⦁ Nitrous Oxide is up 63%.

⦁ Acidification of the oceans has increased by 26%.

⦁ The human population has gone from 1 to 8 billion.

⦁ Energy consumption has increased 40 times.

⦁ The extinction rate is 100-1,000 times greater than the geological norm.

⦁ By 2030, 20% of all species will be extinct.

Indeed, the Anthropocene has another name: the Sixth Mass Extinction.

Krakauer is one of my top 5 favorite authors. I love his work. Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town is his only so-so book.

Examples:

- Into Thin Air: covers the most deadly Mt. Everest disaster of its day

- Into the Wild: follows an unusual hermit who fails to live off the land in Alaska

- Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith: covers polygamy in an American small town

- Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman: covers a superstar athlete who dies in Afganistan

You get the pattern: these are pretty unusual people.

Therefore, if he wanted to write about rape, then he should have written about an extraordinary case of rape and dug deep on that.

Example: the Suryanelli rape case in India, where a girl was allegedly lured with the promise of marriage and kidnapped. She was allegedly raped by 37 of the 42 accused persons, over a period of 40 days. It's going to India's supreme court. It's a HUGE case that would have been perfect for Krakauer to explore.

If he preferred something in the USA, he could have found a high-profile rape case to focus on. For example, he could have focused on the 1993 rape and murder of 16-year-old Elizabeth Pena and 14-year-old Jennifer Ertman in Houston, Texas. Of the six people convicted, five were sentenced to death. Now that's a Krakauer-like story to sink his teeth into.

Moreover, he could have used that case as a springboard to talk about the general problem of rape in America.

Instead of doing what he normally does (laser-focus on person/event/group), he takes the shotgun-blast approach: he covers MANY rape cases in Missoula. As horrific as they all are, it's sad to say that none of them count as truly extraordinary (like the two rape cases I mention above). Instead, they are pretty straightforward rape cases, with all the headaches, trama, and nuances that such cases have.

Besides the graphic detail (which is useful), there's a lot of he-said-she-said, which would have been fine if he had focused on one extraordinary/famous case, but when you're covering lots of rape cases, it gets a bit repetitive.

Here are some analogies to help explain why this book departs from his other books; imagine if:

- Into Thin Air had been about tales of hikers who die in the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

- Into the Wild had been about many random people who try to live off the land - and some succeed and some don't.

- Where Men Win the Glory had been about the many soldiers who tragically die in Iraq due to friendly fire.

Such books would be informative (as Krakauer always is), but they would lack that laser-focus that Krakauer excels out. They would lack a clear protagonist and an extraordinary event to cover. That's why "Missoula" isn't as engrossing as Krakauer's other books, which all deserve 4-5 stars.

I hope that Krakauer's next book goes back to his tradition of finding extremely unusual people/situations and delving deep into them.

AUDIOBOOK: I listened to the audiobook, which was read by a woman, which is unusual. Usually, most audiobooks are read my someone with the same gender as the author - and sometimes even the same accent (e.g., Michio Kaku's books have a man with a Japanese accent read it). Perhaps the audiobook producer thought it would be more effective for a woman's voice read about rape. Regardless, she's an outstanding narrator.

Before sharing my thoughts of this book, I'll share my background and experience to illustrate my expertise, ignorance, and bias.

Background on the reviewer

I've spent many weeks backpacking in the winter or in winter-like conditions. For example, when I did a round-trip on the Continental Divide Trail, I walked across Colorado in May. When you're in the Rocky Mountains in May, it sure looks and feels like winter, even though officially it's spring. The mountains are buried in snow and freezing temperatures are the norm.

My most memorable winter trip was when Lisa Garrett and I did a 4-day backpacking trip in Yosemite during Thanksgiving (late November). You can see some photos from that snowy experience.

I've also climbed many snowy peaks, such as nearly all the peaks in Cascade Mountain Range (e.g., Mt. Rainier, Mt. Hood, Mt. Baker, Mt. Adams, etc...), as well as snowy mountains outside the USA, such as Mont Blanc.

Despite all these situations, I have only once been in a true winter survival situation. That was in late March 2006 when Maiu and I got lost in the Olympic National Park. I've wanted to write about that life-threatening experience for a while years, but until I do, let's just say that we almost died. We spent two nights (one of which snowed on us) in a diabolical ravine. We both ended up with frostbite, but we got out on our own.

Another close call was when I was snowshoeing in Idaho for the day with Julia, my Ukrainian girlfriend at the time. We got lost as the sunset and kept walking until we ran into a man running a snowplow at 3:00 a.m. We were walking the wrong way and he took us back to safety.

Therefore, it was with great interest that I read Winter in the Wilderness. Here are the pros, cons, and verdict of the book.

- Deborah Bräutigam wonders 'Will Africa Feed China?'

- Books by Philippe Tapon

- Amazon's Kindle Paperwhite eReader Review - a super ebook reader

- Russian Professor reviews The Hidden Europe

- Difference between Hike Your Own Hike and The Hidden Europe

- The Arrivals Documentary is Complete Bullshit

- The Drunkard's Walk book review

Your comment will be deleted if:

- It doesn't add value. (So don't just say, "Nice post!")

- You use a fake name, like "Cheap Hotels."

- You embed a self-serving link in your comment.