Reviews

You won't find reviews of Hike Your Own Hike or The Hidden Europe here (that's a lie: there's one review for The Hidden Europe). Instead, this section is for my review of other books, especially nonfiction books, which I comprise 95% of my reading. I occasionally review clothes, movies, a politician, a gadget, or anything else that looks promising.

I've put my best reviews here, but if it's not enough, then you'll find hundreds of reviews on Amazon. I am one of the top 10,000 reviewers on Amazon with over 1,500 helpful votes. And yes, I can review your product if you'd like. Just contact me to see if I'm interested.

I’ve read most of Michio Kaku’s books. I always enjoy them. His newest, The Future of Humanity, is his best. Still, there are parts that I disagree with.

He covers the topics that every futuristic geek loves to devour. The book is divided into 3 parts:

1) Leaving Earth

2) Voyage to the Stars

3) Life in the Universe

Each part has several chapters, covering topics like:

• Mining the heavens

• The challenges of terraforming Mars

• How the moons of gas giants and even comets can become gas stations of the future

• How robots can colonize the universe

• The pros and cons of various starships

• Transhumanism

• Advanced civilizations

• Time travel

I usually dislike books that are a collection of unrelated essays but Paul Theroux’s newest book, Figures in a Landscape: People and Places, is an exception.

When writers compile their essays it’s a sign that they:

- Are lazy.

- Have nothing new to say (e.g., writer’s block).

- Need money.

Many who reviewed Tim Ferriss’s book, Tribe of Mentors, called it a “money grab.” It’s when a popular author wants some quick cash so he pumps out garbage knowing that his fans will eat whatever crap he spews out.

I expected Theroux’s latest book to be just like that. I was ready to skip chapter after chapter. However, I rarely skipped.

The chapters are pulled from his articles in The Washington Post, Harper’s Bazaar, the Guardian, the Smithsonian, New York Times Magazine, and others.

Naturally, many chapters are travel essays. Several cover Africa but others discuss Ecuador and Hawaii. He critiques Henry David Thoreau, Joseph Conrad, and others.

Some of the best parts were the most unexpected: his interviews with Elizabeth Taylor, Robin Williams, and a Manhattan dominatrix.

He ends with a chapter about his dad and why he wants to thwart his future biographers (which is a bit conceited to believe that someone will write his biography).

If you’re a Paul Theroux fan and/or you like travel writing, you’ll enjoy Theroux’s latest, which you can pre-order now. It comes out May 8, 2018.

VERDICT: 8/10 stars.

Disclosure: I received a free advanced copy from the publisher to review.

“Imagine running 84 marathons. Consecutively.”

That’s what running legend Scott Jurek asks you to do in his newest book, North: Finding My Way While Running the Appalachian Trail.

It comes out April 10, 2018.

Warning: if you know nothing about Jurek and Appalachian Trail records, then there are spoilers in this review.

I have mixed feelings about Timoleon Amessa's Saving Africa book. The author is from Cote D'Ivoire but he's lived in the UK for decades.

What I liked

- He says that African leaders ought to take responsibility for its problems.

- He doesn't blame foreigners for everything.

- He spends half the book offering solutions.

- "Democracy is a logical and fair method. It is not rocket science and it is not magic either." (Many argue that Africans are too immature/savage for democracy)

- African countries should focus on the agricultural sector first.

- “Neighboring countries envied Côte D’Ivoire. West Africans rely on agriculture, but Houphouët-Boigny’s policies made a difference because the economy was partly operated by private Western agro-industrial companies.

What I didn't like

I enjoyed watching Black Panther in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The crowd was into it. So was I. It's a fun Marvel Studios movie. If you love superhero movies, you'll love Black Panther.

There are no spoilers in this review.

What I loved

I loved how Black Panther challenges stereotypes. Examples:

- Tough women. Yes, with Wonder Woman and Black Widow, it's not an original idea. Also, the stereotype of a tough black woman is nothing new. But it's still nice to see.

- Most blacks have natural hair. This is a big issue among the black community in the US but Africans are still into artificial hair and chemical treatments. It's nice to see a movie that celebrates natural black hair. There's a scene when a woman complains about her "ridiculous" wig.

- Afro-futurism is an inspiring concept.

My wife's criticism

My wife, who is from Cameroon, gave the movie 8/10 stars.

There's one thing that she disliked. When the white CIA man wakes up, the black female doctor says, "Don't scare me like that, colonizer."

Although the theater filled with Tanzanians laughed, Rejoice did not.

She said, "Some Africans would like to say such things to whites but they refrain out of politeness. Now that they see it in a movie, they may do it more often."

She added, "Blacks would hate it if you called them 'slave' or 'nigger.' Calling a present-day white person 'colonizer' is equally bad. You're using a term of a bygone era on people living today who had nothing to do with colonization or slavery."

I understand her point. I just don't care. I know it's just a joke.

Africans often say to me, "Hey white man!"

Even though this does not bother me, it irritates the fuck out of many whites who work or volunteer in Africa. They said, "They would hate it if they go to Eurasia or the Americas and people say, 'Hey black man!'"

Frankly, I don't care because I know Africans don't mean it in a bad way.

The one terrible idea

The movie has one dangerous idea that will reinforce this dangerous and stupid idea:

Gavin Evans has written a pseudo-scientific book, Black Brain, White Brain: Is Intelligence Skin Deep?

Gavin Evans has a Ph.D. in politics. However, this book is about genetics, race, and intelligence. Some people may feel he’s not qualified to write such a book, but I disagree. You don’t have to have a diploma in a subject matter in order to have an educated opinion on it.

Still, he dares to write, “Even the finest scientific minds are capable of coming up with ridiculous theories when tackling subjects beyond their own calling.” (Loc 154)

For example, James Watson, co-discoverer of DNA’s structure, said he was “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours—whereas all the testing says not really.”

Evans thinks the Nobel-Prize-winning Watson shouldn't "tackle subjects beyond his calling," but somehow, Evans feels it's acceptable for him to do so. That sounds like arrogance or hypocrisy—or both.

Of course, I'm also "tackling subjects beyond my calling" by reviewing this book about genetics and intelligence. But as I said from the beginning, I don't have a problem with Evans (or anyone) debating things outside of their "official" realm of expertise. It's just that I dislike it when young people aren't allowed to voice opinions "because they have no experience."

I am annoyed that Evans doesn't see the hypocrisy of his criticism of Watson and other intelligent people.

Are IQ tests useful?

Are you a mapaholic? Do you just love to scrutinize maps? If so, I've got the book for you.

In 2018, Alastair Bonnett released New Views: The World Mapped Like Never Before: 50 maps of our physical, cultural and political world.

I adore maps and I soaked up all 50 maps.

It's not available as an ebook, which is fine since the colorful book is designed to be flipped through, touched, and examined.

You can see a few sample maps on the book's Amazon page.

My 14 favorite maps from New Views

Let's look at my 14 favorite maps in the book.

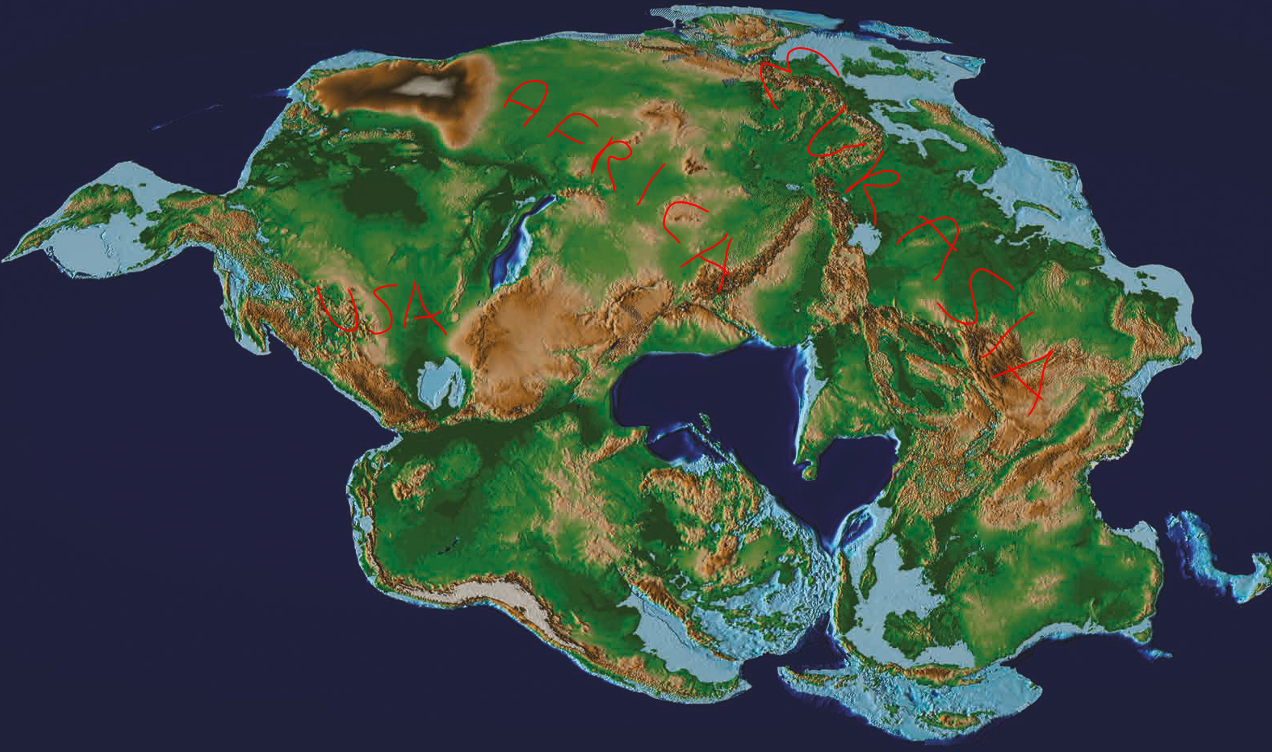

Definitely, my favorite overall is the Pangea Ultima map. The name is terrible. It implies that it's ultimate and final resting places of the continents. It's not. They will continue to move for at least another billion years. Still, it's interesting to see where we're headed. We're going to rejoin the continents again! Drive to see your friends.

David Ogula's Shedding Black Africa's Burden says many things I wish I could write in my upcoming book about my tour through all 54 African nations. Because I'm white, the politically correct police would crucify me if I repeated his statements, even though they are true and fair.

Ogula shows how Africans bear much of the responsibility for the state of their continent.

He offers solutions.They often raise more questions. The devil is in the details. He should have spent less time pointing out Africa's flaws and more time explaining how exactly Africa can shed its burden.

Still, it's a good start.

Rejoice is from Cameroon, so she is thrilled that the first creature that America sent into orbit was from Cameroon.

The creature was named Enos. He was a chimp from Cameroon. He flew aboard the Mercury-Atlas 5 on November 29, 1961. Enos logged three hours and 21 minutes in space. He paved the way for the first American orbital flight three months later.

I’m a fan of space exploration and astronomy. I’m an even bigger fan of the privatization of spaceflight, so I’ve been following the news fairly closely.

Still, just like I didn’t know about Enos the chimp, Christian Davenport’s upcoming book, Space Barons: Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos, delivers plenty of facts I didn’t know about.

If you’ve meticulously followed the headlines, I suppose there’s little new in Davenport’s book. Test yourself.

Did you know that . . .

Surviving Kidnappers: Precautions, Influence, Strategic Tools is an excellent book for anyone who worries about being kidnapped.

From 2013-2018 I traveled to all 54 African countries, including all the ones where kidnapping is a serious risk. Although I took precautions, I wish I had read this book before my trip.

The 2022 book teaches you how to prevent a kidnapping in the first place. For instance, whenever getting into a taxi (or any car), take a photo of the license plate (and the driver) and then email it to a friend. Tell the driver that you’re doing this so that he doesn’t come up with any bright ideas to make an unnecessary detour.

His advice is sound, including:

- Review of Noam Chomsky's 'Global Discontents' book

- Donald Trump’s First and Last 100 Days

- 8 Questions for Dave Hall, author of Winter in the Wilderness

- Review of idoneapps for unlocking Samsung and iPhone

- A Troublesome Inheritance book by Nicholas Wade

- Are Racists Crazy? A book by Gilman and Thomas

- Walking the Nile book by Levison Wood

- Climate Change and the Health of Nations book by McMichael

- Chibok Girls book by Helon Habila

- The New Black Middle Class in South Africa book by Southall

Your comment will be deleted if:

- It doesn't add value. (So don't just say, "Nice post!")

- You use a fake name, like "Cheap Hotels."

- You embed a self-serving link in your comment.