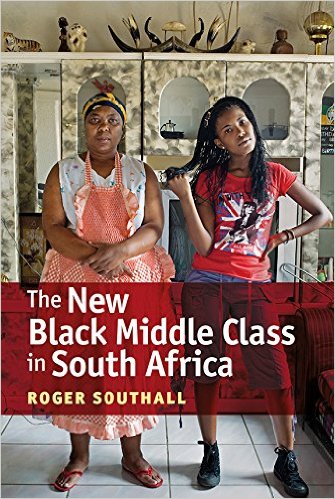

Books about South Africa are sometimes racially biased. The New Black Middle Class in South Africa is not. The author, Professor Roger Southall, writes a level-headed, dispassionate analysis of the emergent middle class in South Africa.

After spending half a year all over South Africa and having picked up over 100 hitchhikers (98% were black), I learned a lot about the racial tensions in South Africa. I saw strong parallels with the USA. Although I was born in 1970, I imagine that South Africa is where the USA was in the first 10 years after aparteid (1965-1975).

Today, even though blacks hold the political power in democratic South Africa (because just 8% of the voters are white), many still blame much of their misfortunes on whites. For instance, their dismal literacy rates of 100 years ago are often faulted on the colonial period.

Southall traces the rise of the black middle class and the force of literacy. In 1911, South Africa's first census concluded that 6.8 percent of its blacks were literate. Before we're quick to blame the white colonists for this low figure, let's remember that prior to the arrivals of the whites, no sub-Saharan society (except Ethiopia) had ever invented writing.

Throughout the 20th century, schools became more common throughout Africa. Today, 94% of South Africans are literate. This has helped fuel the rise of the middle class.

South Africa's literacy rate is much higher than other sub-Saharan countries that had far less intense colonization than South Africa. The average youth literacy rate in the sub-Sahara is just 71%. For young women in sub-Saharan Africa, the rate remains dismally low at 65%.

According to the 2016 UIS estimates, the literacy rate for young men and women is a mere 16% in Niger and below 30% in Afghanistan, Guinea, Mali, and South Sudan (only Afganistan is not in the sub-Sahara). If colonialism is to blame, then why is South Africa (having been far more colonized than those other countries) doing so much better on the education front?

In 1970, 2.7 million black children were in [South African] schools. By 1988, it was 7 million; a third of university students were black.

Today, blacks are the majority of students and the majority of the university administrators. They run the show. Still, given the ongoing 2016 university protests, the students are more dissatisfied than ever.

It's getting harder for South African students to blame the whites for their frustration, but some still do. For example, one student placed a piece of shit on the head of the statue of Cecil Rhodes. Eventually, after much protests, they removed the statue. Now everything is so much better.

Not.

The rise of black middle class is transforming South Africa. One of the most prominent aspects is the so-called "black diamonds." These are the high-income blacks who can now afford luxuries that few in Africa can afford. It's having an impact on how they view the culture of their ancestors, according to Southall:

In a 2004 survey, all black diamonds had TVs, 94% had cell phones, 71% had access to a car. Meanwhile, 86% believed in lobola (brideprice), 75% slaughtering animals to thank the ancestors, 47% in traditional healers, and 71% felt guilty about owning so much when other family members were poor.

I don't want to give the impression that Southall's book is all about education. It's not. And I certainly don't want to give the impression that it's making the points that I'm making about the state of the university system. No, the author is much more politically correct than I am.

If you want a fascinating survey and analysis of the rising middle class, then read this book. Southall takes an nuanced view of the state of the middle class in South Africa. He astutely points out the promise and risks that they face.

If South Africans play their cards right, they will show the rest of Africa how to become a high-income nation. If they play it wrong, then they'll become just another African headache.

VERDICT: 8 out 10 stars.

If, however, you're not in the mood to read a book, then watch the Fanie Fourie's Lobola movie. Unlike Southall's book, this movie is full of laughs. Nevertheless, it's still profound in its ability to capture the tension between the old and new generation in South Africa. Watch the trailer...

The publisher sent me a free advanced copy for review.